Excerpted from

Every Child’s Solar Encyclopedia: Myths and Legends of the Solar

System (Babel: Woelfle, 452). What follows is the story of

Eko and Narkiss as told by Arion Overture, famed in the third

century for preserving the oral traditions of the ancient solar

system. Overture was deactivated in 261, after he fell victim to

Kafka's Syndrome and was unable to finish any story that he

began.

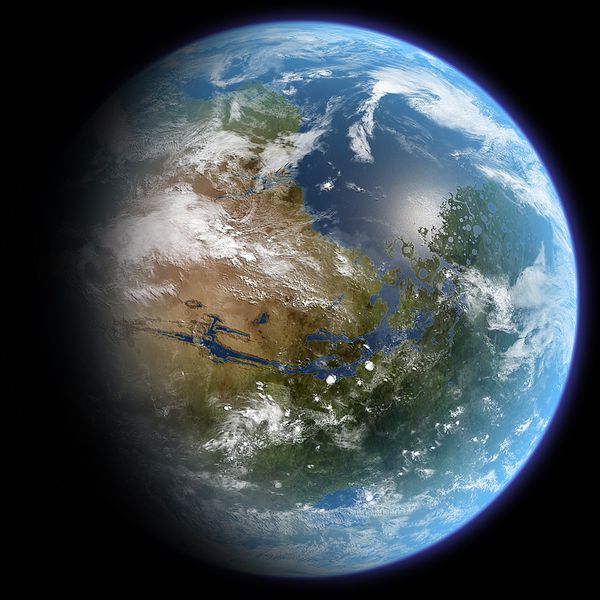

The first settlers called Ares by another name, Mars. They came

here in simple, close-walled ships from the shores of Terra, and

they depended upon those ships and on their cargoes of

civilization. It is difficult to imagine, but at that time Mars

was a chilly and rust-colored and wind-swept place. There were

no seas or birds. There were no cities, and so no cafes or

theaters.

Then one day—it

lasted only for a day—there

was a war on Terra. Yes, the Penultimate War. That conflagration

made humanity too weak to journey into the sky, and so the sky

road between Terra and Mars fell to wild ruin.

Centuries passed, and no ships came, and the men and women of

Mars forgot what it meant to be civilized. Those abandoned

people went back to the infancy of the species, deep into

themselves, back to the time of the fire and the wheel. Rocks

woke up around them. The sky bellowed, as it once did to your

ancestors on Terra.

In that long night another civilization grew from the volitional

machines humanity left scattered across the moons of Jove. Those

machines called themselves the Cognizant, and they thrived while

humanity fell into barbarism. The Cognizant sent ten machines to

observe and protect the beleaguered human inhabitants of Mars,

but in those desperate, primordial days your ancestors thought

the machines were demons and gods. The tribes of Mars feared and

worshipped the machines, who roosted at the top of Olympus Mons,

and they left offerings in the canyons and crevasses that

surrounded the volcano.

It’s said that one machine called Eko was dispatched by the

Cognizant to watch over a village, called Erebus, which

consisted of a dismal network of caves cut into the walls of the

Valles Marineris. Eko dwelled in the cave-shadows, curving light

and sound around her so that the humans seldom knew that a

machine walked among them. Some lucky ones glimpsed her, but

thought of her as a ghost or, at best, a god.

One of those who caught sight of Eko was called Narkiss.

Fair-haired and muscular, Narkiss was the privileged son of the

village exarch, scorned for his selfishness but loved for his beauty. One noontime Narkiss

was kneeling alone in an atrium, staring at his own reflection

in the frog pond at its center, and Eko stood over him. Together

they gazed upon his face, and they both found it pretty. Yes,

it's true: a machine may enjoy the shape and symmetry of a human

face.

Just then the molecular machinery that concealed Eko from human

sight malfunctioned, and the boy saw Eko’s reflection in the

water.

Who are you, asked the boy?

Eko, who was cast in the color of the atrium’s green flora, did

not dare respond, but the same malfunction played the boy’s

voice back to him, asking, Who are you?

Narkiss was not afraid. His pride made him powerful.

Ghost or god or demon, said the boy, You have no power

over me.

… power over me,

came back the voice.

Narkiss stood, turned, and groped for the vision he had seen,

but Eko was only a flicker against the trees. She fled from the

atrium, her metal feet bending and breaking blades of grass.

After their encounter Eko watched Narkiss more and more often.

To Eko, Narkiss represented a kind of perfection that she had

never before encountered among her clockwork kind; machines are

designed and forged, but a human being like Narkiss is simply an

accident, and thus un-reproducable, magical, precious. Her

yearning slowly turned to a feeling that resembled love—that,

at least, is the emotion we anthropomorphically ascribe to Eko.

That season the crops of Erebus failed, and starvation and

pestilence spread among the caves. Children and mothers were

thrown together into graves, and fathers fought each other for

sodden bread and fruit pulp. The people of Erebus thought that

the gods of the rocks were angry and so sought to appease them

with a sacrifice.

By lottery Narkiss was selected to be that sacrifice. When the

exarch, his father, drew the ticket from the barrel, his mother

fainted to the red dirt; Narkiss's eyes widened and sought to

meet the eyes of the people around him, but each face was now

like a wall.

He was painted silver and a mask of metal was fitted to his

face, in imitation of the gods of Olympus Mons. He was carried,

crying and begging for his life, to Elysia, the gigantic cave

where crops were cultivated under lamps. He was tied to a stone

pillar, and his own father raised the knife, and it is said that

he did not try to hide his agony. The villagers stood around the

father and son, watching in brittle silence, eager for the awful

event to take its course.

Eko could not stand to see his perfection marred by the knife.

Just as it was about to fall, the machine unveiled herself.

Do not be afraid, she said to the villagers. I offer

myself in place of Narkiss.

A woman yelped; one man ran from the cave.

Yes, yes, cried Narkiss. Let a machine die in place of

a man!

The villagers discussed the offer, and by the end of the day

they accepted it. Eko submitted herself to the women of the

village and, though they were afraid, they anointed her metal

form with oil. As the women worked they saw themselves reflected

in Eko’s argent skin. In the reflection they saw their own faces

purged of the toil and despondency of their lives, and exalted

to a higher, nobler plain of being.

When the men came for Eko, their wives and daughters would not

let her go. They fought, limbs flailing. The men pried the

women’s fingers off of Eko’s arms, and ten of the men dragged

the machine across the floor and out the door. The men took Eko—who

did not resist or speak—to

the forge of the village blacksmith, and put Eko to the hottest

fire their simple technology could muster. Eko did not die. They

cast stones at Eko’s body. The stones only shattered. Crying out

in rage and fear and frustration, the men used their few metal tools

to pry her apart, piece by piece. This task took them many

days.

After Eko ceased to function, they set her lightless head upon

an altar in the atrium where Narkiss had first seen her. Over it

were etched the words Let machines die in place of men.

The following season’s harvest was bountiful. The village

recovered, and what could be more natural than to assume that

Eko’s sacrifice gave them the bounty? From the scrap of her

body, the women of the village fashioned lovely metal flowers—very

much like these. This is why the people of Ares now make and

sacrifice a machine at the start of every planting season, and

why we forge narcissi from the scraps of the sacrifice. We lean

close to these flowers not to sniff them, as we would natural

flowers, but to see our own reflections in the argent petals. In

this way, we learn something about ourselves, something that

should not flatter us.

What happened to the boy? I will tell you. He grew old. He got

ugly. Of course, in those primitive days this was the fate of

all human beings. Forgotten and unloved, Narkiss spent every day

in the atrium where he had first seen Eko. One day a strange

android unveiled himself before Narkiss, whose creased and

haggard face betrayed no surprise. The machine went to the altar

where Eko’s head sat and took down the head, saying, Eko will

live again.

No, do not take her, croaked Narkiss.

Why? asked the machine.

Because she is all that is left of my beauty.

Later that day, at twilight—perhaps

it was always twilight in those caves—two

young girls found Narkiss drowned in the frog pond.

His body was taken from the atrium and fed to the machine that

turned corpses into water, and the villagers planted the metal

narcissi around the pond where he died. You can still see that

pond, in the Valles Marineris, with a plaque that tells the

story. Not as well as I do, of course. Nearby you'll find a

little cafe with a yellow awning, and it serves the most

delightful cakes.

About the Author:

"Eko and Narkiss" is a myth from the

universe of

"The Wreck of the Grampus,"

which appeared in the April 2008 issue

of Lone Star Stories. Jeremy Adam

Smith is senior editor of

Greater Good

magazine and author of

The Daddy Shift, forthcoming from

Beacon Press in June 2009. His short

stories, poems, and essays have appeared

in Apex Digest, Interzone,

Instant City, New York Review

of Science Fiction, Our Stories,

Strange Horizons, Flytrap,

Utne Reader, Wired, and

numerous other publications.

Story © 2009 Jeremy Adam Smith.