Melissa comes home

with fingers broken, hair gummy with clay dirt, crushed worms,

mulch. Bramble-slashed, root-tripped, both knees skinned, ankles

turned—nights afterward, muscle memory jars her awake: legs

pumping, lungs heaving, hands crabbed to claws, head turned to

glance behind.

*

* *

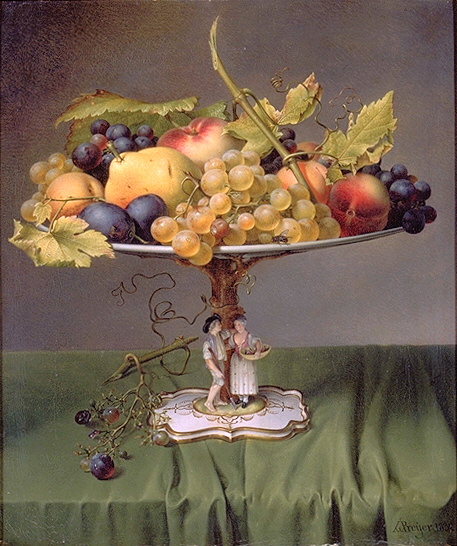

They had said: touch

nothing here. The apples, redder than your shoes—the berries

dark as drowning—eat of them and they will eat of you, as sure

as teeth, as hungry for your heart as flame for tinder, and

you'll waste for want of them, your heart as hungry for them as

tinder for a flame.

So she'd been

warned. She didn't heed. Despite or because of that, they'd let

her go. Turned her out for the game of it, like coursing. She

would run herself to ground.

*

* *

Five days home, her

mother starts to chide. You have to eat, she says. Again she

says, It's been two weeks. Where have you been?

Hands clumsy with

the bandaging, Melissa tries. Toast and eggs, soup and

sandwiches, ice cream. It chokes her like a collop of wet

sponge. Retching, she dashes down the hall.

Her mother calls out

after her, Is this about some boy?

*

* *

Her mother drives

her to the hospital. She's clucked at, administered a pregnancy

test, hooked up to a saline drip, sent home. While she takes a

bath, her mother's in the kitchen, baking mocha brownies with a

soft fierce concentration: Melissa's favorite, before. She

thinks to write Welcome Home on top with icing, then thinks

better.

There's nothing

wrong with her, the nurse had said. These things do tend to

pass. Don't draw attention to it. Just—keep an eye on her. Still

not keeping food down in a week? Bring her back in.

Stepping out into

her robe, Melissa's startled at the sharp wings of her ribs and

hipbones, the sudden rosary the light tells on her spine. The

brownies cloy like carrion, crumble in her throat like char.

*

* *

The therapist's

office looks like her grandmother's living room. The chairs are

pretty much the same, as is the gradient of light. Respectively:

plush corduroy, repressive.

You aren't eating?

says the therapist.

Can't, says Melissa.

Would you like to

talk about it?

Melissa's mouth

opens and the memories come: lights flickering through trees;

the smell of ozone and wet greenery; a thread of music, slick

and itchy, that fishhooked her and reeled her in and through —

Better you didn't

let me leave at all, she thinks, than leave like this.

Melissa's mouth

shuts.

The therapist's

fingers steeple like a cartoon mastermind's. The lilies on her

desk are fake.

*

* *

Her suitcase won't

hold much. Toothbrush, hairbrush, mascara, deodorant, nightgown,

change of clothes. She muscles that heap down, then squeezes in

a sketchbook, charcoals. Two or three novels. A half-read

magazine.

Her mother's leaning

in the doorway. This isn't a punishment, she says. It's best for

you. If you won't eat—

Melissa whirls

round, dizzies. Yells, to keep in focus, keep from blacking out:

I. Can't.

The room starts

slipping anyway. Her mother snaps: Believe it or not, I was

fifteen once—

Melissa comes to on

the floor, her mother tipping sips of orange juice down her

throat. It draws a cold line down the length of her, then comes

up warmer, acid. Melissa shuts her eyes.

*

* *

Her room isn't like

a hospital room, not quite. There's some effort toward being

welcoming, upbeat: bright walls, plump blankets, a potted

hyacinth. Out the window, May grass verges on a distant treeline.

Amid dandelion constellations, the browsing trapezoids of deer.

The window's painted shut.

Melissa makes the

rounds. The shower heats up fast; the bed is firm. In the closet

is a cabinet with snacks. She manages a saltine before she

starts to gag. Crossing back to the window, she sets her jaw,

glares out toward the trees. Swallows hard and holds her breath.

Her splinted fingers clench on nothing. Flip a coin, she thinks.

And it stays down.

*

* *

She keeps to herself

at group. The other girls are different. She is the only one

among them unafraid of the multivitamins, the protein drinks,

the peanut butter crackers. They have tricks, though, for the

weekly weighings, which she learns. Where to hide the rolls of

quarters. How to hold your breath. It's not enough. She weighs

one-oh-seven, one-oh-five, one-oh-four, one-oh-four, one hundred

dead. Her belt's run out of holes. Her teeth feel strange. The

insides of her cheeks peel off like molting skins. The eyes in

her mirror are the eyes of one who wanders outside looking in.

*

* *

Eventually they find

out she's been burying her zinc pills in the hyacinth. Nurses

hold her down, come at her with a cup of chocolate milk. It

tastes like nails, coins, keys. Dry heaves jackknife her around

herself. She's too exhausted to fight, too dehydrated to cry.

Waking, there's a

tight pain in her elbow-crook. The IV crouches on her like a

feeding spider, languid and self-satisfied. She pulls it out.

There's blood. They gauze her up and stick the IV in the other

arm. She pretends to sleep. Then she does sleep.

*

* *

She wakes. A smell

has hauled her headlong from some dream. Lush and blowsy, this

smell, black and green. Her eyes prickle. Her skin. Her blood

stabs her with some memory— blind longing grapples, roots,

metastasizes—gone. Something in the air, the light? She pulls up

the sheet and sniffs its edge. Not that.

Minding the IV, she

sits. Her vision swims and clears. Movement snags her eye. She

turns. The rose-print curtain bellies, calms. High wind rushes

in the distant trees. Snowflakes—no, chips of white paint—eddy

on the floor. She stands.

The window is open.

The moon is very bright.

About the Author: