All the Daughters of This

House

by Nicole Kornher-Stace

I.

Once upon a time

the house’s bones

were strong:

stone stacked on

stone from clay earth to slate roof,

walls fashioned

waist-thick to ward daughters

from the reach of

thieves and wind and kind-eyed wolves –

daughters named for

virtues they were bound,

by force of name, to

lack.

Hope withered on her

attic cot,

rising to jar jam,

chop wood, sweep floors

arms tough as

sugarcanes, inked dark with maps on maps

(in palimpsest: this

vein a silverlode, a river, a many-legged road;

that scar a

snowfield, an oasis, or an isle)

gaze to the horizon

she named ships

she never, outside

dreams, would sail.

Grace slipped

through the ice behind the house

(a jealous lake: it

snaps its fingers and

your fish go

belly-up, your boats go down.

It hoards its

drowned.)

and her dripping

ghost paced orchard-rows, perched in

peach-trees, singing

all her might-have-beens,

black ice clacketing

like dropped knives in her hair.

Chastity palmed up

scoops of mud beneath the reeds

and buried all the

minnow-children

(monsters’ brats or

saints’, her lips are sealed)

doomed to swim too

early from her womb.

Oakleaves and

daisies for their coverlets

and a cradle-song to

fresh-turned, bone-cold earth:

go to sleepy,

little baby, mama’s here.

The house wept from

all its windows

and longed for

gingerbread and gumdrops

to sugar-paste on

its stone skin

and lure the hungry

mouths, the clumsy hearts, the running feet –

thinking: some might

flee, or not be hoodwinked,

but some, perhaps,

might stay.

II.

Once upon a time

the house's stones

loosened like teeth.

Its windows slouched

in waves. By now

the shingles dulled

like molted scales. Beside the lake

squat tombstones

hunched and clustered,

pale and dark as

grapes. Two daughters slept under

a sagging roof,

daughters named for beauty,

raised to charm.

Grown tall,

they parcelled out

the house between them:

Lily brought her

husband; Violet her books. Together

they baked layer

cakes and meatloaf, planted

marigolds. One

pushed the vaccuum while the other

dusted frames. Each

one swore

that she was happy —

the bluestocking, the housewife —

each feigned to

scorn the other's choice. Though when alone,

Lily locked herself

away in Violet's library

and stretched her

cramping mind against

philosophy,

astronomy, comparative linguistics.

At her baby's cry,

she set her sister's spectacles

beside the lamp,

slid her finger back into

its wedding ring,

and plastered on a smile.

Unaware that Violet,

alone, was given to

let down her hair,

wear Lily's cocktail dress, her bracelets.

That gathering her

niece's empty swaddling to her breast

she'd practice

lullabies to children

no-one would ever

give her:

go to sleepy,

little baby, mama's here.

The house shifted in

its sleep

and wished for a

belt, a skirt, a cape of thorns

as long as tongues,

as green as sin

for men to crash

against like robins at a windowpane

and with all their

expectations fall away.

(That daughters

might pick berries from

their lonesome

bones. That crows might tithe their eyes.)

Behind which those

it guarded might find peace.

The house snarled

with its graveyard breath

and the wolves fled

from the door.

III.

Once upon a time

the house shakes in

its skin

cellar to shingles,

and a window – two –

the last ones left –

blow out. That one was close,

the people murmur,

stacked like nesting dolls

(the smallest

snugged in the next-smallest's arms,

the largest's back a

shield)

in a fireplace, a

bathtub, under stairs.

The house, gone

loose and bawdy in decrepitude,

holds its doors

slack as any sheela-na-gig

to whatever wind may

come; but its grasp, too,

is just as clever,

and its old laddered spine is sound.

(The lake is dry.

The fish are combs of bone.)

One daughter lives

here now:

strong in her way,

like all the daughters gone before,

she knows the shape

and taste of loss, and lack, and hope,

of compromise and

need.

She flinches as the

impacts near,

but takes the baby

in her arms (the measure of her strength

the distance she can

carry, can protect, the ones she loves)

and races air-raid

sirens through high walls of smoke.

Hands cupping little

ears against the screams she sings

go to sleepy,

little baby, mama’s here.

The house stretches

ungiving cellar-roots

and yearns for

stilt-high, tree-high, star-high chicken legs

to bear it up and

send it on

shedding black mold

and bricks and chimneysoot

over the broken

roads, the bloodied dead

only pausing once:

to stoop (like any witch)

and reach long nails

to claim its own,

the last kernel of

its fragile weary windburnt heart;

to nestle it and

lullaby as soft as snow

as the fires build

bright towers on all sides

and the bombs drop

down like golden apples in the dark.

About the Author:

Nicole Kornher-Stace was born in Philadelphia in 1983,

moved from the East Coast to the West Coast and back

again by the time she was five, and currently lives in

New Paltz, NY, with one husband, three ferrets, the

cutest baby in the universe, and many many books. Her

short fiction and poetry has appeared or is forthcoming

in several magazines and anthologies, including Best

American Fantasy, Fantasy Magazine, Ideomancer, GUD,

Goblin Fruit, and Idylls in the Shadows,

and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Her first

novel, Desideria, is available for purchase on

Amazon. She can be found online at

www.nicolekornherstace.com or

wirewalking.livejournal.com.

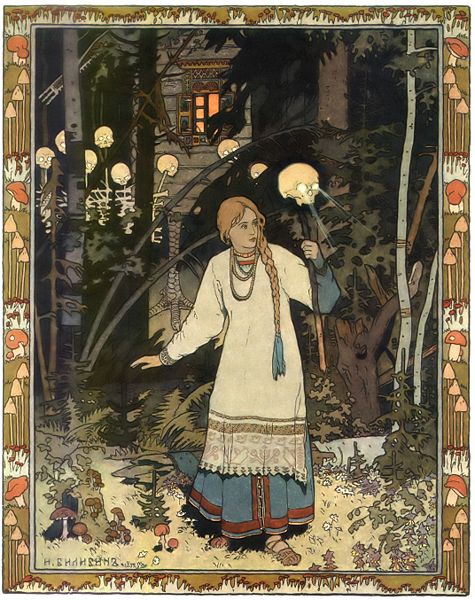

Poem © 2008 Nicole Kornher-Stace. Painting by Ivan Bilibin, 1899.

|