Conjuring

by M. Thomas

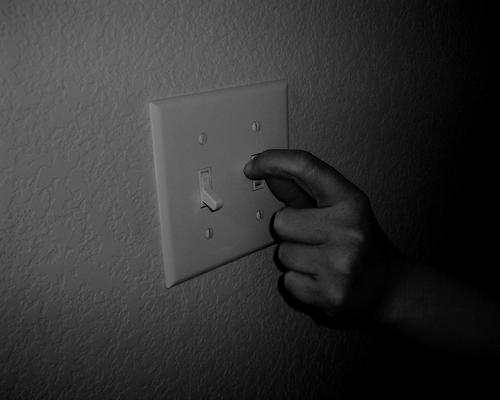

She waits until Jonathan has left for work -- he despises this ritual -- and then on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on, off, on off, on, off.

She

moves into the kitchen, which is the closest sink to the back door.

Washes seven times. Up and

down the sides of each finger five times. Turn

hands under the water five times to rinse. Another

dollop of soft soap. Repeat.

From there it is a safe trip to the garage, and the ritual of locking and

unlocking the car door. Seventeen

times. Except for the bedroom light

switch, odd numbers are the preferred pattern.

The

maid won't stay. She is very kind,

but doesn't speak English much. She

gestures to various things. The

light switch. The sink.

The remote control on the key chain.

She wrinkles her brow, puts out her hands to plead for the right word.

She only knows how to say "Diablo."

You are bedeviling yourself.

Sarah

knows this already, knows that her mind substitutes repetitions for a sense of

safety.

The

new maid is old. She has a thick

accent, but speaks English well. In this age of accuracy, Sarah thinks she

should recognize the accent from TV or a movie.

Is it the cockney of a PBS Presents "David Copperfield"?

Is it the Russian shtick from the latest spy movie?

It is undefinable.

The

maid's name is Gert. Perhaps German.

Although one day she mentions New Zealand.

She wears flowered dresses like the type seen in old photos of World War

II. Pulls her hair back in a bun,

and nary a lock escapes. She is a

bustler, like Sarah's mother was when she needed to be busy enough to forget.

Gert bustles to and fro, always looking busy, busy, always with a rag in

her hand, dusting anything that happens to lie along her path.

And she watches Sarah, who is used to being watched by maids, watches her

at the light switch, at the sink, in the garage with the car, brushing her hair

(seventy-seven strokes), rearranging the silverware, turning a vase when it has

been replaced on the shelf slightly to the left of where it should be.

Finally,

after three weeks, Gert says, "How you conjure!

I haven't seen this type of conjuring since I was a very, very young

child."

It

stops Sarah in her tracks over by the couch.

The TV remote is not set quite right on the table, but it will keep a

moment.

"What

do you mean by that? What do you

mean about the conjuring?"

Gert

smiles. She has small, harmless

teeth. (Teeth are brushed three

times, eleven strokes top and bottom.)

"This,

with the light switch, and the washing of hands.

This is conjuring. My

grandmother did this, after our Paw-Paw was killed.

Oh, how she conjured him!"

Sarah

reaches down and moves the remote two inches to the right.

She will not ask the how or why. She

knows them already, as if they were secrets she was keeping from herself.

"And did it work?" she says.

Gert

shrugs. "There was a day we

could not find her, and then she didn't come back.

I always wonder, wherever he was, was he conjuring her too?

And in the end did she go to him, rather than bring him back to us?"

"Have

you ever conjured?" Sarah asks.

"I'm

not lonely for the dead," Gert says, then moves on to the upstairs

bathroom.

That

night, Sarah tells Jonathan, "Gert says it's conjuring."

He

rolls his back to her. "That's

good. I'm glad the maid is feeding

you some nonsense like that."

"What

if it isn't?"

"What

if you just took your pills like the doctor said, and it all went away?" he

replies. "Oh, I know.

Then you wouldn't have anything to do all day."

Jonathan

sleeps. Sarah gets up to wash her

hands.

*

* *

Tildy

was a pretty thing, Sarah's little doll, except that she fidgeted too much and

even at four only spoke in grunts, and she had a wide face with glassy eyes that

seemed only to notice the shine on things.

They

never took Tildy to events where Sarah's father needed to be seen with family.

There

was a day they were hosting a special business dinner, and no sitter could be

found to keep Tildy upstairs, so Sarah was left in charge.

Tildy slipped away, slippery eel, grunting and pointing and wide-eyed,

and appeared in the doorway of the dining room drooling happily at her

cleverness. One of the women

shrieked.

Sarah's

father grabbed Tildy by the arm and dragged her into the hallway, with Sarah

watching like a silent fetch near the stairs.

Her father shook Tildy, and shook Tildy, and shook Tildy until her head

bobbled -- "Don't you do that!

Don't you do that!" Later,

Tildy threw up, and her eyes bled. After-dinner

drinks were ruined by the arrival of the ambulance.

Sarah

remembers this until it is deep night, and the soft soap is all gone.

Her fingers are cold, her flesh red.

Something moves in the corner of her eye.

She looks up at the kitchen window, across the long, green lawn.

Something slips away behind a tree, a little bare foot, the edge of a

summer dress. The cicadas, which had

fallen silent, swell up like static.

Now

she knows. For the first time, she

begins to flick the switch for the back porch light.

Thirty-seven feels like the right number.

She turns the deadbolt. One,

two . . .fifty-five, fifty-six, fifty-seven. There

are many light switches in the house. Many

sinks. Many locks. When

Gert arrives, she has not slept.

"How

long did it take your grandmother?" Sarah asks.

"Fifteen

years," Gert says.

And

so, she conjures.

Copyright © M. Thomas 2004

Photo Copyright © Eric Marin 2004

About the Author:

M. Thomas lives in Texas. Her fiction has appeared in Abyss & Apex, Strange Horizons, and Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet.