|

|

The Behold of the Eye

by Hal Duncan

The Imagos of

Their Appetence

"The Behold of

the Eye," Flashjack's laternal grandsister (adopted), Pebbleskip

had told him, "is where the humans store the imagos of their

appetencewhich is to say, all the things they prize most

highly, having had their breath taken away by the glimmering

glamour of it. Like a particular painting or sculpture, a

treasure chest of gold and jewels, or a briefcase full of

thousand-whatever notes, or the dream house seen in a magazine,

a stunning vista seen on their travels, even other humans.

Whatever catches their eye, you see, she'd said, is caught by

the eye, stored there in the Behold, all of it building up over

a person's lifetime to their own private hoard of wonders. The

humans say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, you know,

but as usual they've got it arse-about; what they should be

saying is something else entirely."

"Beauty is in

the Behold of the Eye," Pebbleskip had said. "So that's where

most of us faeries live these days."

*

* *

Flashjack had

hauled himself up beside her on the rim of the wine-glass he was

skinnydipping in, shaken Rioja off his wings, and looked around

at the crystal forest of the table-top he'd, just a few short

hours ago, been born above in a moment of sheer whimsy, plinking

into existence at the clink of a flippant toast to find

himself a-flutter in a wild world of molten multicolour

mandalas wheeling on the walls and ceiling, edges of every

straight line in the room streaming like snakes. He'd skittered

between trailers of wildly gesticulating hands, gyred on

updrafts of laughter, danced in flames of lighters held up to

joints, and landed on the nose of a snow-leopard that was

lounging in the shadows of a corner of vision. He'd found it a

comfy place to watch one of the guests perform an amazing card

trick with a Jack of Hearts, so he'd still been hunkered there,

gawping like a loon at the whirl of the party, and making little

flames shoot out of his fingertips (because he could), when

Pebbleskip came fluttering down to dance in the air in front of

him.

"Nice to get out

once in a while, eh?" she'd said. "Hi, I'm Pebbleskip."

"I'm... Flashjack," he'd decided.

"What's in a while? Is it like

upon a time? And out of what?"

Her face had

scrunched, her head tilted in curiosity.

"Ah,"

she'd said. "You must be new."

Since then she'd

been explaining.

*

* *

The funscape had

settled into solidity now, with the drunken, stoned and tripping

human revellers all departed into the dawn, the host in her bed

dead to the world, but through a blue sky window to the morning,

sunlight slanted in to sparkle on the trees of wine-glasses and

towers of tumblers all across the broad plateau of the breakfast

bar. It painted the whole room with a warm clarity which

Flashjack, being newborn, found easily as exciting as the

acid-shimmered kaleidoscope of his birth. The mountains and

cliffs of leather armchairs and sofa, bookcases and shelves,

fireplace, fridge and counter were all very grand; the empty

bottles had such a lush green glow to them inside; the beer-cans

with the cigarette-butts were seductively spooky spaces, hollow

and echoing; even the ashtrays piled high with roaches had a

heady scent. As Pebbleskip had been explaining, Flashjack had

been exploring. Now he dangled his legs over the edge of the

wine-glass alongside her, surveying his domain.

"You mean they'd

keep all this in their Behold?" he said. "Forever?"

"Nah, probably

not," said Pebbleskip. "Mostly they'd think this place was a

mess. The rugs are nice, and it's kind of cosy, but they'd have

to be a quirky bugger to Beholden this as is. No, if this place

was in the Behold it'd probably be a bit more... Ikea."

Flashjack nodded

solemnly, not knowing what Ikea meant but assuming it

meant something along the lines of goldenish; the

sunlight, its brilliant source and bold effect, had rather

captured his imagination.

*

* *

"You'll see what

I mean when you find your Beholder, said Pebbleskip, which

you'll want to be doing toot sweet. I'd take you home with me,

see, but two of us in the same Behold? Just wouldn't work, ends

up in all sorts of squabbles over interior design; and the

human, well, one faery in the Behold of the Eye, that just gives

them a little twinkle of imagination, but more than one and it's

like a bloody fireworks display. They get all unstable and

artistic, blinded by the glamour of everything, real

or imagined, concrete or abstract. They get confused between

beauty and truth and meaning, you see, start thinking every

butterfly-brained idea must be true; before you know it they've

gone schizo on you and you're in a three-way firefight with all

the angels and the demons, them and their bloody ideologies."

Pebbleskip sounded

rather bitter. Best not to ask, thought Flashjack.

"I'm not saying

it can't work sometimes," she said, "but a lot of humans can't

handle one faery in their Behold, never mind two. Mind

you, if you find one that's got the scope . . . well, it can be

a grand thing . . . for all the arguments about where to put the Grand

Canyon."

She looked kind of

sad at this, Flashjack thought.

"Anyway, I'm

off. My Beholder's too fucked from the come-down just now to

know I'm gone, but she'll miss me if I'm not there when she

wakes up."

And with that

Pebbleskip whirled in the air, and swooped to slip under the

door, Flashjack darting after her, crying, "Wait!" as she

zipped across the hallway and into the bedroom. He poked his

head round the door to find her standing on the host of the

party's closed eyelid.

"How do I find

my Beholder?" he said.

"Use your

imagination," she said.

"But how will I

know if it's the right human?"

"They'll know

you when they see you," she said.

And disappeared.

*

* *

The Azure Sky and

the Golden Sun

Using his

imagination, because he wasn't terribly practiced at it and

couldn't think what else to do, simply took Flashjack back to

his birthplace in the kitchen/living-room, where he sat down

dejectedly with his back to the trunk of a bonsai tree on top of

the fridge, gazing out of the window at the azure sky and the

golden sun rising in it, at the backyard of grass and bushes and

walled-in dustbins, the blocks of sandstone tenement ahead and

to the left, all with their own windows facing out on the same

backyard, some windows lit, some dark, but each with different

curtains or blinds, flowerpots on a ledge here or there, and the

odd occupant now and then visible at a window, making coffee,

washing dishes, pottering, scratching, yawning. Using his

imagination then, because he was a fast learner, had Flashjack

quickly off his arse, his face pressed through the glass,

realising the true potential of his situation.

There were a lot

more rooms in this world than he'd previously considered.

*

* *

Slipping through

the window with a pop, he spiralled up into the air to find yet

more tenements beyond the rooftops, roads and streets of them,

high-rise tower-blocks in the distance, a park off to his right,

a ridiculously grand edifice to the west which, a passing

sparrow explained, was the university building, in the

mock-Gothic style, and not nearly as aesthetically pleasing as

the Alexander "Greek" Thomson church across the road from it.

He snagged the sparrow's tail, clambered up onto its back, and

let it carry him swooping and circling over the "West End" of

the "city" (which was, he learned, called Glasgow), nodding as

it sang the praises of its favourite Neo-Classical

architecture. The sparrow had a bit of a one track mind though,

and Flashjack wasn't getting much of an overall sense of the Big

Picture, so with a thank you, but I must be going he

somersaulted off the bird to land on a chimney, considered his

options for a second then, rising on the hummingbird blur of his

own wings, he hovered, picked a random direction, and set off at

his highest speed.

An hour later he

was back where he'd started, sitting on the chimneypot,

prattling excitedly to a seagull about how cool the Blackpool

Tower is.

*

* *

"Ye want to be

seeing the Eiffel Tower, mate," said the seagull. "Now

that's much more impressive."

"Which way is

that?"

Having been

instructed in all manner of astral, magnetic, geographical and

meteorological mechanisms for navigation, in a level of detail

that raised suspicions in Flashjack that all birds were rather

obsessively attached to their own pet subject and lacking in the

social skills to know when to shut the fuck up about it,

he set out once again, returning a few hours later with a very

high opinion of Europe and all its splendoursincluding, yes,

the Eiffel Tower.

"Better than Blackpool by a long shot, eh?" said the seagull.

"What's Blackpool?" said Flashjack.

It was at that

point that Flashjack, after a certain amount of interrogation

and explanation from the seagull, who had met a few faeries in

his day, came to understand that it would be a good idea to find

a human to get Beholden by ASAP.

"See, they do

the remembering that yer not very good at yerself," said the

seagull. "Memory of a gnat, you faeries. If I'd known ye

weren't Beholden yet, I wouldn't have sent ye off. Christ

knows, yer lucky ye made it back."

"How so?"

"Yer a creature

of pure whimsy, mate. What d'ye think happens if there's no one

keeping ye in mind? Ye'll forget yerself, and then where'll ye

be? Nowhere, mate. Nothing. A scrap of cloud blown away in

the wind."

*

* *

Flashjack looked

up at the azure sky and the golden sun, which he'd only just

noticed (again) were really rather enchanting. He really didn't

want to lose them so soon after discovering them, to have them

slip away out of his own memory as something else took their

place, or to have himself slip away from them,

fading in a reverie to a self as pale as those sensations were

rich.

"Go find yer

Beholder, mate," said the seagull. "Yer already getting

melancholic, and that's the first sign of losing it."

Flashjack was

about to ask how, when his now rather more active imagination

suggested a possible plan; to get Beholden obviously he'd have

to attract someone's attention, catch their eye so as to be

caught by it. Being a faery, he reasoned, that shouldn't

actually be too difficult. Over in the park, he'd noticed in

passing, a whole grass slope of people were lazing in the

afternoon sun, drinking wine, playing guitars or just lying on

their backs, clearly the sort of wastrels who'd appreciate a bit

of a show. So with a salute to the seagull, Flashjack was off

like a bullet, over one roof, then another, a gate, a bridge, a

duck pond, and then he was directly above the slope of

sun-worshippers, where he stopped dead, whirling, hovering,

spinning in the air, reflecting sunlight from his whole body

which he'd mirrored to enhance the effect, so that any who

looked at him and had the eyes to see might imagine he was some

ball of mercury or magic floating in the sky above them. Or

possibly a UFO.

He wasn't sure who

he expected to Beholden him, but he did have a quiet hope that

they'd be someone of relish and experience, the Behold of their

Eye full to bursting with the things they'd seen and been struck

by. In fact, it was Tobias Raymond Hunter, aged nine months,

currently being wheeled by his mother and escorted by his

toddling older brother, who looked up from his pram with blurry,

barely-focused vision and saw the shiny ball in the sky.

*

* *

A Rather Strange

Kind of Room

There was a pop,

and Flashjack found himself in what he considered a rather

strange kind of room. The Behold seemed to be the inside of a

sphere, its wall and ceiling a single quilted curve of pink

padding, which Flashjack, being a fiery type of faery, born of

drink, drugs and debauchery, was not entirely sure he liked.

Added to this, it was velvety-silky-smooth and warm as skin to

the touch; in combination with the pink, it was like being in a

room made of flesh, which Flashjack, frankly, found either a

little creepy or a little kinky. He wasn't sure which, and he

had no specific aversion to kinky as such, but the whole

feel of the place . . . he just wasn't sure it was really him.

Still, the three most striking features of the Behold very much

were: above his head wheeled coloured forms, simple

geometric shapes in basic shades, but radiant in hue, positively

glowing; beneath his feet, layer upon layer of snow-white

quilts, baby-blue blankets and golden furs formed a floor of

luxuriously cosy bedding wide enough to fit a dozen of him; and

in front of him was a great circular window, outside of which

the sky was bluer than the bright triangle circling overhead,

the sun more golden than the fur between his toes.

What with the

breast/womb vibe, the primary-coloured mobile and the oh-so-cosy

bedding, it didn't take Flashjack too long to figure out where

he was. It wasn't quite what he had been hoping for, he had to

admit, but there was a certain encompassing comfort to the

place. He flopped backwards onto the bed, wondering just how

far down into the cosiness he could burrow before hitting the

bottom of the Behold. As an idle experiment, just out of

curiosity, he imagined the mobile overhead changing direction,

spinning widdershins instead of clockwise. It did.

"Okay," he said.

"I

think this'll do nicely."

*

* *

"No, no, no,"

said Flashjack, "this just won't do."

It wasn't the sand

or the water that was the problem per se so much as the fact

that they were in entirely the wrong place. It was all very

well for Tobias Raymond Hunter to love his sand-pit and his

paddling pool, and for the bed to have changed shape to

accommodate these wondrous objects in the Behold of his Eye, but

the boy clearly had no sense of scale; they took up half the

bloody room. And to have them both, well, embedded in

the bed, that was just silly. At the moment the bed was cut

into a thin hourglass by the sand-pit and the paddling pool; add

to that the fact that more and more of the remaining space was

being eaten up by Lego bricks, lettered blocks and other such

toys, and Flashjack was now left with only the thin sliver

between sand-pit and paddling pool to sleep on. He wasn't a big

fan, he'd discovered, of waking up spitting sand or sneezing

water because he'd rolled over in his sleep and been dumped in

the drink or the dunes. No, it just wouldn't do.

He sat on top of a

lettered block and studied the situation for a while then set

his imagination to work on it. When he was finished, the

paddling pool covered the whole area of the floor that had once

been bed. Within that though, the sand-pit was now a

decent-sized island with the bright blue plastic edge of it

holding back the water. In the centre of the island, the Lego

bricks and lettered blocks were now a stilted platform, with

blankets, quilts and furs forming his bed atop it, and a jetty

reaching out over the sand and water, all the way to his great

window out into the world.

"That's a damn

sight better," said Flashjack.

*

* *

"Da' si' be'r,"

said Tobias Raymond Hunter, giggling as Flashjack performed his

Dance of the Killer Butterfly for the tenth time that

day. He never tired of it, it seemed to Flashjack, but then

neither did Flashjack, as long as the audience was

appreciative. As Tobias Raymond Hunter patted the palms of his

hands together in an approximation of a hand-clap, Flashjack

gave an elegant bow with a flourish of hand, and started it all

over again.

"Da' si' be'r!

Da' si' be'r! Da' si' be'r!" said Tobias Raymond Hunter.

His father,

entirely unaware of Flashjack's presence and convinced that his

son was referring in the infantile imperative to his own (Da)

singing (si) of what was apparently Toby's favourite

song, Teddy Bears' Picnic (be'r) was

meanwhile launching into his own repeat performance with

somewhat less enthusiasm. As much as he was growing to hate the

song, he did put his heart into it, even using Toby's own teddy

bear, Fuzzy, as a prop in the show, though Toby, for all his

enthusiasm, seemed to pay little attention to it until halfway

through the third chorus (Flashjack, by this time, having

finished his eighteenth performance (his Dance of the Killer

Butterfly being quite short) and decided to call it a day),

whereupon the previously ignored Fuzzy became an item of some

interest.

In the Behold of

the Eye, Flashjack was guddling goldfish in the paddling pool

when Fuzzy came dancing out of the forest of sunflowers that now

obscured most of the pink fleshy walls.

*

* *

The bear was one

thing, but this was getting ridiculous. Flashjack knew what was

to blame; it was that bloody bed-time story that Toby was

obsessed with. Oh, it might seem all very innocent to his

parents but, like Toby's brother, Josh, who he shared his

bedroom with and who groaned loudly each time the rhyme began --

that's for babies! -- Flashjack was getting deeply tired

of it. No one had ever told him (as far as he remembered) that

the Behold of the Eye might turn into a bloody menagerie of

fantastic animals, flions soaring through the air on their great

eagle wings, manes billowing as they roared, little woolly meep

getting underfoot everywhere you go, rhigers charging out of the

trees at you when you least expect it, giraphelant stampedes...

and the rabbull was the last straw. The rabbull is quite

funny, half bull and half bunny, with horns and big ears that go

flop. Funny. Right. Because when it sees red, it'll

lower its head, and go boingedy-boingedy-BOP! Well,

Flashjack had had quite enough bopping, thank you very much, and

did not consider the rabbull funny in the slightest.

"We're going to

have to do something about this, Fuzzy," he said, standing on the

jetty looking back at his Lego-brick tropical jungle-hut, and

rubbing the twin pricks on his arse-cheeks where he'd been

bopped from behind. "They're bloody overrunning us," he said.

"Fuzzy," said

Fuzzy, whose vocabulary wasn't up to much.

Flashjack turned to look out the window of Toby's eye, at the azure sky and the

golden sun, which were particularly new to him today. He

wished he could get out there, get away from the zoo of the

Behold even just for a few hours, but Toby, it seemed, was not

as . . . open as

he once was. Last time Flashjack had decided to pop through the

window he'd found himself nursing a bopped nose. That's another

problem with being a creature of pure whimsy, you see; when your

Beholder grasps the difference between real and imaginary, as

they're bound to do sooner or later, they decide that a faery

must be one or the other, mostly the other. Flashjack gazed at

the blue and gold.

"See that?" he

said. "That's what we need. Room."

Not just a

room, he thought. But room. Space.

He looked down at the water below, sparkling with the blue of

the sky even though the ceiling above, which it should have been

reflecting, was pink, and he wondered if . . . with just a

little tweak . . . if he could draw that blue sky out of it . .

. it shouldn't be that

hard for a faery . . .

And the Behold of

the Eye was, after all, a rather strange kind of room.

*

* *

In The Land of His

Stories

Flashjack leapt

down from the giraphelant's back and flicked his flionskin cloak

back over one shoulder as he strode across the savannah to the

cliff then, dipping so his feathered headdress wouldn't catch on

the lintel, entered the darkness of Fuzzy's cave.

"I've had an

idea, mate," he said cheerily. "I've had an inspiration."

"Fuzzy," said

Fuzzy pathetically.

If Flashjack had

thought about it he would have regretted his words; The poor

bear had been getting tattier and glummer ever since his own

inspiration had been lost (or so Toby's parents claimed;

Flashjack suspected foul play on the part of Josh, sibling

rivalry and such), and Toby's infantile attention slowly turned

to other objects of desire. So inspiration was rather a

button-pusher of a word for Fuzzy, who was fading week by week

and now convinced that the process of being forgotten would

eventually end with him disappearing entirely. If Flashjack had

thought about it he might have tactfully rephrased his boast.

Flashjack, however, partly because he was a faery and dismissed

such fatalism with a faery's disregard for logic, and partly

because he was a faery and had little sense of the impact of his

words on others, simply breezed into the cave and hunkered down

before his old friend, a glinting grin on his face.

"Fuzzy, me boy,"

he said, "if you want to call me a genius right now, feel free to

go ahead and do so, or if you want to wait until you hear my

Plan, then that's just as good. Either way, I cross my heart

and hope to die, stick a needle in my eye, but fuck me if I

haven't found a solution to your problem."

"Fuzzy," said

Fuzzy.

"Why, thank you,"

said Flashjack. "Okay, come with me."

*

* *

It had been a

while since Fuzzy had visited the island, so when the good ship

Jolly Roger docked at the new jetty and the monkey crew

leapt off to moor her soundly, despite the three day voyage, the

general glumness of the bear, and the actual purpose of the

visit, Flashjack blithely forgot the fact that they were

actually there to do something in his keenness to show

just how much improvement had been made. The old jetty now

had a troll under it, the island now had its own lakewith an

island on it, with a castle, and a beanstalk going up to the

clouds, and there's a castle there with a giant in it and

everything!

"Fuzzy," said

Fuzzy impatiently.

"Okay, Okay," said Flashjack and took him in to his stilted jungle-hut (which was

now all but covered in vines, barely recognisable as Lego-bricks

and lettered blocks), shifted the bicycle with stabilisers

(which Toby's brother, Josh, refused to let him ride), sat him

down on the pouffe (which Toby had seen at an aunt-and-uncle's

house and thought a strange and wondrous thing, this chair with

no back), took a seat on the ottoman himself (which Toby's

parents had in their bedroom and which, being half

backless-chair and half treasure chest, was even more wondrous

than the pouffe), and began to explain his Plan.

*

* *

Toby, Flashjack

had realised, had become utterly enchanted with the fairy

stories once read to him at bedtime, now devoured over and over

again by Toby himself. He'd come to desire adventure, to yearn

for it, such that the Behold of the Eye was blossoming with new

wonders every day. He wanted a dreamworld to escape to, the

place that Puss-in-Boots and Jack-the-Giant-Killer and the Three

Billy Goats Gruff lived. These were the imagos of his

appetence, so here they were in the Behold of the Eye. But

something was missing in the land of his stories.

"He wants a

monster," said Flashjack. "I've looked out of the window as he

checks under the bed, looks in the closet, or opens his eyes in

the dead of night and sees scary shapes in the patterns in the

curtains. It frightens him, of course, so he can't admit

he wants a Monster, but it thrills him too. You can't have a

land of adventure without the giants and trolls and the Big Bad

Wolf, but the ones he's Beholden, well, they're straight out of

the cartoons. I just know he wants something more."

"Fuzzy?"

"Well that's

where you come in."

*

* *

The sky overhead

darkened with nightfall, the sun descending from the wheeling

mobile of moon and stars and planets to sink below the horizon

and let the shadows escape from beneath the canopy of trees and

slink up and around them, shrouding the island till only the

flickering glow of the great pyre of a night-light on the beach

was left to light Flashjack and Fuzzy as they stood down by the

water's edge.

Flashjack reached

up into the darkness, up into the sky, and plucked a sliver of

moonlight, kneaded it and rolled it out like plasticene then

blew on itpuff!to make it hard as bone. He did

it again, and again, kept doing so until there was a pile of

moon-bones there before him. He grabbed the silver of the surf

and made a pair of scissors to cut Fuzzy open, then one by one

he put the moon-bones in their place. Then he caught a corner

of the night between thumb and forefingers and peeled away a

layer of it which he snipped into shape and started sewing onto

Fuzzy with a pine-needle and vine-thread, a second skin of

darkness to go with his skeleton of moon-bones.

Flashjack was very

proud when he sat back and looked at the Monster he had created.

*

* *

A Perfectly

Ordinary Kouros

The books arrived

slowly at first. For a long time it was jungles with pygmies

and dinosaurs, deserts with camels and wild stallions, forests

with wolves, mountains with dragons, oceans with sea serpents.

There was one burst of appetence where Flashjack woke up one day

to find the blue sky ceiling of the Behold just gone, inflated

out to infinity, the planets and stars of the mobile suddenly

multiplied and expanded, scattered out into the deep as whole

new worlds of adventure, and spaceships travelling between them,

waging inter-galactic battles that ended with stars exploding.

He would fly off to explore them and get drawn into epic

conflicts which always seemed to have Fuzzy behind them, or

Darkshadow as he now preferred to be called (which Flashjack

thought was a bit pretentious). He would find magical weapons,

swords of light, helmets of invisibility, rayguns, jet-packs,

some of the snazziest uniforms a faery could dream of, and with

Good on his side he'd defeat Fuzzy and send him back to the

darkness from whence he came. After a while he began to find

himself waking up already elsewhere and elsewhen, a life written

around him, as an orphan generally, brought up in oblivion (but

secretly a prince). This was a lot of fun, and for a long time

Flashjack simply revelled in the fertility of his Beholder's

appetence, the sheer range of his imagos. For a long time,

whenever he woke up in his own bed he would leap out of it and

run down the jetty to look out the window in the hope of

catching a glimpse of whatever book Toby was reading now, some

clue to his next grand adventure. For a long time it was simply

the contents of the books that were Beholden by the boy. Then,

slowly at first, the books themselves began to arrive.

*

* *

It's a very nice

bookcase, Flashjack thought to himself, but why a boy of his age

should be Beholdening bookcases is frankly beyond me. I mean, a

chair can be a throne, a table can hold a banquet, a wardrobe

can be a doorway to another world, but a bookcase? A bookcase is

a bookcase is a bookcase. It's not exactly bloody

awe-inspiring.

He paced a short

way down the jetty towards the island then wheeled and paced

back, stood with his hands on hips staring at the thing. It

wasn't ugly with its dark polished wood, clean-lined and solid.

It was even functional, he had to admit, because he could

replicate a whole bundle of the buggers from this one, and he

could really use something to store the mounds of books --

leatherbound tomes, hardbacks with bright yellow dust-covers,

cheap paperbacks with yellowed pages and gaudy coversthat

were piling up everywhere these days, appearing in his bed, on

the beach, in rooms in the castles, clearings in the forests,

caves in the mountains; he'd found a whole planet of books on

his last interstellar jaunt. But functional was not an

aesthetic criteria that Flashjack, as a faery, had terribly high

on his list of priorities; it was well below shiny and

nowhere near weird.

It was, in his

considered opinion, actually rather dull.

"It's safe," said

a voice behind him.

Flashjack turned,

but no one was there.

*

* *

The statues began

to appear not long after the Voice Incident. There had been

statues appearing for years, of course, along with the busts and

reliefs, even a whole colossus at one pointToby had clearly

gone through a romance with all things archaic as a side-effect

of his absorption in the adventures of ancient mythbut where

before the statues had just seemed another facet of the cultural

background, set-dressing for the battles with minotaurs,

chimaera, hydra and what-not, these were different. Flashjack

didn't notice it with the first one; it seemed a perfectly

ordinary kouros of the late Classical tradition, in the

mode of Lysippos. He didn't notice it with the second one,

which looked fairly similar but carried a certain resemblance in

the facial features to statues of Antinous commissioned by the

Emperor Hadrian, though he'd clearly been rendered here as he

would have looked in his early adolescence. He didn't even

notice it with the third one, which was quite clearly a young

Alexander the Great. It was only with the fourth, the fifth,

the sixth and the seventh that Flashjack, starting to wonder at

Toby's . . . consistency of subject matter, took a quick flight out

to his galleon built of bookcases, went down into the captain's

quarters and, after a few hours cross-referencing the Beholden

statues with the images in the books (from which, of course, in

a previous period of idle perusal he had learned everything he

knew about Lysippos, Antinous and Alexander (and if you're

wondering how he managed to remember such things when he

couldn't even remember the sun in the sky, well, Flashjack was

by now a faery on the verge of maturity, beginning to reach a

whole new level of inconsistency) ) and realised the

discrepancies.

On a factual

level, he could find no traces of such statues actually existing

out in the world. On a stylistic level, there were a number of

deviations from the classic S-shape of the contrapposto pose,

hips cocked one way, shoulders tilted the other. And on a

blindingly obvious level, which had not occurred to Flashjack

simply because he was a faery and had little concept of decorum

never mind prurience, the sculptors of the Classical period did

not, on the whole, tend to give their statues erections.

"Our little boy

is becoming a man," said Flashjack to himself, smiling because,

as a faery, he also had little concept of heteronormativity.

*

* *

"My power grows

every day, old friend," said Fuzzy.

"Now's not the

time for the Evil Villain routine," said Flashjack. "I'm worried

about Toby. Books and statues, statues and books. And now

this."

They walked through the library that had appeared over the last

few weeks, coalescing gradually, as shelves appeared, thin

slivers in the air at first then slowly thickening, spreading,

joining, walls doing the same, until the whole place had just .

. . crystallised

around Flashjack's island home, sort of fusing with the

structure that was already there, almost matching it, but... not

quite. Flashjack's bed was on a mezzanine floor now (with the

Children's and YA Section) which hadn't even existed before.

Downstairs from this, in the centre of the structure and facing

the entrance (flanked by twin flions), where his bed should

have been, was a counter-cum-desk thing that ran in a square,

four Flashjacks by four Flashjacks or so; with the computer and

the card files and the date-stamp and the oven and the

dishwasher and so on, clearly it was meant to fuse the functions

of librarian's desk and kitchen area. Beyond this was the main

library-cum-living-room (which mostly consisted of the

SF/Fantasy Section). There were even male and female bathrooms,

which Flashjack avoided; he quite enjoyed pissing where there

was snow to piss in, but he'd tried the whole dump thing once

and just wasn't impressed with the experience. And everywhere

there were the bookshelves, everywhere except the Romance

section, which was like a museum with all its statuary.

All in, the place

wasn't much bigger than Flashjack's hut, so it wasn't a grand

library; in fact, it reminded Flashjack quite strongly of the

public library he often saw out of Toby's eye, the boy spending

so much time there these days; it seemed that he had come to

adore his literary sanctuary so much that it had become his

dream home, usurping the more Romantic jungle-hut of Flashjack's

preference. Now Flashjack was quite okay with his own

reimaginings of Toby's imagos, but now that the tables were

turned he was feeling rather put out. It just wasn't healthy, a

teenage boy Beholdening a dream home full of books. And a

haunted one at that.

"You don't get

it," said Fuzzy. "My power grows every day, old friend."

"Look, I'm just

not in the mood to play Good versus Evil today, Fuzzy. I heard

the Voice again this morning, over in the Romance section.

It's safe. It's safe. That's all it keeps saying. There's

something wrong with our Beholder."

"You don't

understand," said Fuzzy. "That's what I'm worried about.

Whatever's happening to him is making me stronger, more vital.

More intense. I'm his monster. And I feel like a fucking god

some days."

Flashjack turned

to look at Fuzzy, who had stopped asking to be called Darkshadow

a while back, and would now simply laugh bitterly and say: I

have no name, Flashjack. His skin made out of the night

itself, he seemed a black hole of a being, an absence as much as

a presence.

"And

I have . . .

urges," said Fuzzy. "I want to burn this place to the ground, I

want to smash those statues to dust, and I want to feast on that

Voice, make it scream itself out of existence and into silence."

Fuzzy was getting

rather over-dramatic lately, thought Flashjack.

*

* *

The Ghost of an

Imago

Most weekdays it

rained corpses, faceless, gurgling blood from slit throats.

Flashjack would sit in the library, listening to the pounding on

the roof, or stand to look out the floor-length windows and

watch the bodies battering the jetty, falling out of the sky

like ragdolls of flesh, slamming the wood and bouncing,

slumping, rolling. He'd watch them splash into the water, sink

and bob back up to float there, face-down, blood spreading out

like dark ink until the sea itself was red. The troll under the

jetty, who never showed himself these days, would be a dark

shape in the water after the showers of death, grabbing the

bodies and dragging them down into the depths; Flashjack had no

idea what he was doing with them, wasn't sure he wanted to know.

The lake on the

island was on fire. The island on the lake was choked with

poisonous thorns. The castle on the island was in ruins. At

the top of the beanstalk which was now a tower of jagged

deadwood, bleached to the colour of bone, the giant sat in his

castle, eyes and lips sewn shut, and bound into his throne by

chickenwire and fish-hooks that cut and pierced his flesh.

Flashjack had tried to free him, but every time he tried the

wire grew back as fast as he could cut it. Flashjack wept at

the giant's moans which he knew, even though they were wordless,

were begging Flashjack to kill him; he just couldn't do it.

The worst were

those that Flashjack could kill, the torture victims who

were crucified, nailed to stripped and splintered branches,

bodies dangling in the air, all the way up and down the thorny

tower of the dead beanstalk. He recognised the faces he had

seen through the window of Toby's eye, laughing in crowds, he

knew that these were imagos of tormentors tormented, imagos of

vengeance, and when he'd tried cutting them down they simply

grabbed for him with madness and murder in their eyes; but he

couldn't suffer their suffering, not in the Behold of the Eye,

which was meant to be a place of beauty, and so he put them out

of their misery with his knife as they appeared, most weekdays,

one or two of them at a time, just after the rain of corpses.

*

* *

When the body of

the Voice manifested, it was that of Toby himself, or of a

not-quite-Toby. Where Toby was dark-haired, not-quite-Toby was

fair. Where Toby was pale, not-quite-Toby was tanned. Where

Toby was slight, not-quite-Toby was slim. Where Toby wore jeans

and a tee-shirt, trainers and a baseball jacket that just didn't

look right on him, not-quite-Toby wore exactly the same clothes

except that on him they looked totally right. Where Toby moved

with the gangling awkwardness of a growth-spurted adolescent not

yet in full control of all his limbs, not-quite-Toby rose from

the chair in the library's living-room with the limber grace of

an athlete, an animal. He strolled up to Flashjack, where he

stood at the entrance, one hand reaching out to lay the book he

had been reading down on the countertop of the librarian's desk,

the other reaching out to stroke the purring gryphon guard at

Flashjack's side, in a fluid move that ended with an offered

handshake.

"It's safe," he

said.

"Why is it safe?"

asked Flashjack, shaking his hand.

The ghost of an

imago, the imago of a ghost of Toby looked up at him with a wry

smile, a raised eyebrow. Something about the causal

self-confidence was familiar to Flashjacka hint of Toby's

brother, Josh, maybe, or someone else he couldn't quite place.

"I'm not gay,"

said not-quite-Toby.

He laughed, patted

Flashjack on the shoulder and turning, plucking his book back

off the countertop, sauntered back to his chair, plumped down on

it and put his feet up on the coffee-table.

"Hang on," said Flashjack, whose curiosity about the word Toby so furiously

scrubbed from his school-bag had led him to some startling

realisations. "I mean, I've seen what Toby looks at when he's wanking, mate. You've only got to look at his"

It was then, as

his hand raised to point and his head turned to look, that

Flashjack noticed the statues in the Romance Section were all

now draped in white sheets, and not-quite-Toby's smile was that

of Josh when he'd bested his little brother easily in a sibling

spat, of the tormentors after Flashjack had put his knife into

their hearts, or of Toby, some days, when he just stood looking

in the mirror for minutes at a time while corpses rained in the

Behold of his Eye.

*

* *

Fuzzy was smashing

the statues with a crowbar that had been matted with blood and

hair when it appeared in the Behold. With every statue that was

smashed, the ghost of an imago, the imago of a ghost of Toby

gave out a scream of blue murder and tried to curl himself into

a tighter ball. With every statue that was smashed

not-quite-Toby was less and less the easy, graceful, carefree

straight boy that Toby wanted to be, more and more another

version of the lad, another not-quite-Toby: one that was not

just dark-haired but dark of eye and fingernail and tooth; one

that was not just pale but corpse-white; one that was not just

slight but skeletal; one that tore at his jeans and tee-shirt

till they hung as rags; one that moved in twisted, warped,

insectile articulations.

With every statue

that was smashed, Flashjack just whispered, no.

"He's killing

us," Fuzzy had snarled. "He's killing himself. They're

killing him. He's killing them. Don't you get

it, Flashjack? Don't you fucking get it? Can't you see what's

being Beholden here every fucking day?"

He'd fought his

way through a five-day hail of corpses that sunk his ship,

hauled himself up onto the jetty with the troll's broken,

bone-armoured body slung over his shoulders, hurled it through

the doors of the library and stormed in, caught the defending

gryphons by the throat, one in each hand, snapped their necks.

Flashjack had roared to the attack, swashbuckling and heroic, a

sword of fire whirling over his head, and been batted out of the

air with a backhand slap.

Fuzzy had grabbed

the crowbar from the coffee table, where Flashjack had been

studying it, worried, and strode into the Romance Section,

ripped the sheet off the first statue. Not-quite-Toby had run

at him in a frenzy of rage, horror, fear, despair, but he'd not

reached Fuzzy before the crowbar swung, connected with the white

marble and shattered it utterly.

Now Fuzzy swung

the crowbar for the last time, shattered the last marble statue

and, as the thin shards of stone flew in every direction, the

last beautiful corpse of Toby's stone-bound desire slumped to

the library floor amid the dust of its thin shell. Fuzzy

grabbed the stillborn imago by the hair and hauled it up so

Flashjack could see and recognise the face, one of Toby's

tormentors but, oh, such a good-looking one. Fuzzy turned on

the wretch of a not-quite-Toby, pointing the crowbar at this

thing now cowered in a corner, hissing, spitting madness at the

revelation of its untruth.

"This is what

Toby wants to be," he snarled. "Aren't you?"

"Fuck you, fuck

you, fuck you, fuck you!"

"You're the

imago made of his self-pity and self-loathing."

"Fuck you!"

"And just what

is it that you are? Inside, beneath the lie? What do you

really want to be? Tell him! Say it!"

The creature

lunged, tears streaming down its face, clawed fingers out.

"I want to be

dead!"

And the shadow

that was Toby's Monster and the most loyal of all his imagos

swung the crowbar in a wide arc, hard and fast, and brought it

down with a sickening crunch upon the skull of not-quite-Toby.

*

* *

"You can't do

this, Flashjack. I can't let you."

"Was your

solution any fucking better? Was it? You thought if you just

shattered the lies, made him face the truth, that would make it

all peachy? That it wouldn't be the final fucking straw?"

Around them the

storm was raging through the Behold of the Eye, a fiery hail of

planet-shards, stars falling from the heavens, smashing

everything beneath it, burning everything it smashed, in an

apocalypse of desire. The ruin of the library burned. The

island itself burned. Every castle and kingdom, every city and

savannah, forest and field, all the Beholden wonders of Toby's

dreamscape burned. Only Flashjack and Fuzzy were able to stand

against the scouring destruction, the one more fiery than the

flame itself, the other darker than the blackest smoke, only

them and the tiny broken piece of jetty that they stood on,

Flashjack firing jets of ice-water into the sky like

anti-aircraft fire, shattering the burning hail above them into

sparks, and desperately trying, at the same time, to focus his

concentration on the pile of bodies that he knelt over.

"I can do this,"

he said. "I can give him something to hold onto, something to

want."

His fingers worked

furiously on the flesh and bone, twirling and tweaking,

squeezing and stretching, two skeletons into one bone, muscle

woven around muscle around muscle then stitched into place.

"He doesn't

want to want," snarled Fuzzy. "He wants to not

want."

"I can make him

want," said Flashjack.

At its core a

heart that had once been not-quite-Toby, its body built of all

the imagos of thwarted yearning, the boy would be beautiful when

Flashjack was finished. He would be all Toby's desire-to-have

and desire-to-be fused into one, and he would be irresistible,

undeniable.

"I can't let you

do that," said Fuzzy. "He wants me not to let you do that."

Flashjack looked

up at the crowbar in the shadow's hand, then up at the empty

darkness where the face should be. Had there been eyes,

Flashjack would have stared straight into them with a fire the

equal of the holocaust around them.

"Does he?" said Flashjack.

And as the shadow

swung, a solid wall of ice smashed up through the wood between

them, sparkling with the blue clarity of the sky but solid as a

storm door, and though the shadow brought the crowbar down on it

like a pick-axe, again and again and again, left a hairline

crack and a smear of red blood, the wall did not break as

Flashjack raised his finished creation up, cradling its head in

his arms, and lowering his face to breathe himself into it with

a kiss.

*

* *

His Prison of

Glass

Flashjack huddled

in his prison of glass, watching the flames ravage the Behold of

the Eye, engulfing everything, even boiling the very waters of

the seas, setting fire to the coral and seaweed and dead fish of

their dry beds. Soon there was nothing to be seen but the fire

or, once in a while, a dark shape striding through the inferno,

stopping to raise its arms, turning, revelling in the

desolation. Flashjack watched this for a long timehe

wasn't sure how long

arms wrapped round his tucked knees, missing

his wings and his innocence. His strange new body was a work of

art, but he wasn't exactly using it for what it was meant; he

should be out there in the Behold, being shameless in his

enjoyment of it, offering Toby an imago of desire unbound. But

it wasn't safe. It just wasn't.

He waited,

expecting Fuzzy to come back and try again to smash his way into

the sanctuary and cage Flashjack had made for himself, turning

water into ice, ice into glass. Fuzzy, however, was too busy

with his new position as king of hell. So he waited, expecting

the flames to burn themselves out any day now, any day,

reasoning that once the broken dreams which fuelled the inferno

were all stripped away to nothing, then the very lack of

anything to care about would kill it; the fire would consume

itself.

The fires of hell

burned on.

*

* *

Flashjack huddled

in his prison of glass, watching the boy outside batter his

fists against it. He buried his face in his crossed forearms,

but it didn't really help; he couldn't hear the screams, which

comforted him a little when he curled up in a ball at night and

tried to sleep, but even when he closed his eyes he could see

this new generation of tormentors tormented, each arriving naked

and afraid, to be broken, mutilated, maimed for days, weeks,

months, and then their skin stripped off, sewn to moon-bone

structures speared into their shoulders until, eventually, they

rose from the carnage of themselves, spread wide their ragged

leather wings and joined the ranks of the tormentors to set upon

the next new arrival.

Occasionally,

something pretty, something beautiful would appear but it didn't

last long; everything else almost immediately smashed and soiled

by the demons, ruined and then burned, only those few imagos

which had appeared inside Flashjack's glass prison had been

spared destruction. There was the last remnants of the jetty,

of course, now reshaped into a little palette bed of driftwood.

On the floor was sand, soft and warm and golden, which had

trickled down one day over his shoulder, as if through invisible

fingers. There was a smooth pebble and a sea shell which

Flashjack held now, one in each hand, wondering if in holding on

to them, in being himself something to hold on to, he was only

perpetuating the pain, if by letting the walls fall and walking

out to let the demons tear apart the last vestiges of desire he

could perhaps bring it all to an end. He couldn't do it.

*

* *

Flashjack huddled

in his prison of glass, his back turned to the horrors of the

Behold, looking out the window of Toby's eye at the azure sky

and golden sun. Then the vision shifted and there was a face,

laughing but with warmth rather than cruelty, a friend mugging

ridiculously, pushing his nose into a pig-snout with a finger.

The boy's life was not bereft of happiness, kindness, joy; his

world had autumn leaves, crisp winter snow, the buds of spring,

and it had summer, hot and shimmering summer days like this when

Flashjack would press his hands up to the glass and yearn to

bring that sky and sun back into the cavernous waste of the

Behold. Toby's friend mouthed something, listened to the

response then laughed, went bug-eyed with his disbeliefno

fucking way, manand Flashjack wondered how his Beholder

could be in a friend's good company, laughing and joking, and

yet still so desolate of desire.

For the umpteenth

time that afternoon, Flashjack lifted the little shard of mirror

that had dropped into the sand in front of him a few mornings

ago. He held it up as close to the glass as he could get it,

angled it this way and that.

When you see

someone with a twinkle in their eye, you must understand, often

that twinkle is their faery flashing a little mirror to see if

you too have a faery in your Behold, a little how-do-you-do?

from one sprite to another. But sometimes what seems like a

twinkle of whimsy might well be a glint of madness, the faery in

the Behold of their Eye sending a desperate SOS in the hope that

someone, anyone, will help.

For the umpteenth

time that afternoon, there was no answer.

*

* *

Flashjack woke

with a start, and rubbed sleep from his face, ran his fingers

through his hair. And felt the dampness of his fingers. And

saw

The Behold of the

Eye was dark and empty, and he was wet from the drip-drip-drip

of the ceiling of his prison of glass which had become a prison

of ice and

as he clambered to his feet and reached out to

touch the wallnow transformed again, losing its form

completely and collapsing, in a rush of water, to soak into the

sand beneath his feet and into the ash beyond. The window at

his back, Flashjack peered into the gloom, but there was

nothing, no fire, no demons, only darkness.

Yes, it's me,

said the darkness, in a voice that Flashjack knew and that, for

a second, frightened him, knowing as he did what Toby's Monster

was capable of. Then he realised there was something different

in its tone, something that was far more awful than the bitter,

raging thing that had smashed the statues, far more terrible

than the dark, despairing thing that had stood above him with a

crowbar and with nothing where its eyes should have been. But

he also knew, somehow, it wasn't a threat.

"You don't want

to kill me," he said.

It doesn't matter

any more. Nothing does.

The words sent a

chill down Flashjack's spine.

"I don't

understand."

The darkness said

nothing, offered no explanation, but it seemed to coalesce a

little, a vague shape, black upon black, that stood back a ways

from Flashjack and off to one side, staring out the window.

Slowly, Flashjack turned, not understanding what he was seeing

at first, a cup of tea held in Toby's hands, the family dog sat

in front of the armchair, looking up at him, people milling in

the living-rooman aunt and uncle visiting, it seemed, and

more

Toby's father in the kitchen at the phone, his mother

getting up off the sofa to make more tea, wiping her eyes, his

father dialling another number, and talking, then dialling

another number, and talking, then dialling another number, and

talking, and Toby was just watching him now, transfixed on him,

though it seemed like he was saying the same thing over and over

again, except now he wasn't saying it at all, just dropping the

phone and burying his face in his hands, and Toby had turned to

stare straight ahead at the TV set with the framed photograph on

top, of Josh.

Then there were

tears running down the window.

*

* *

A Handful of

Forevers

All through the

funeral Flashjack worked. As the car drove them to the church,

Toby looked out to one side, and suddenly there in the Behold

was a shimmering image of the road the car was on, the spot they

were passing, with Josh standing there, sun in his hair, hair in

his eyes, about to step out but not stepping out, caught

in an eternal moment. Flashjack grabbed the road and pinned one

end to the window of Toby's eye, threw the other out into the

ashen darkness as far as it would go, as far as Toby could want

it to go, which was forever, and the fields unrolled from its

verge as far as the eye could see, a moment transformed into

eternity.

*

* *

As the family sat

in the church, oblivious of the minister's mute mouthings over

the boy he'd never, as far as Flashjack was aware, had the

slightest contact with, Flashjack took the frozen moment of a

Josh-who-did-not-step and, grabbing every glint of a spark of a

memory that appeared in the Behold, layered in the smiles and

the strut and the style and the spats and the football trophies

and the record collection and the David Bowie poster and all the

vanity and cockiness and sheer shining brilliance that was

Josh-before-he-stepped.

*

* *

As the car pulled

out of the driveway of the church and, out on the high street,

an old man walking past came to a stop and took his hat from his

head, then stood to attention with a sharp salute for the hearse

of a total stranger, Flashjack grabbed the flood of unspoken

gratitude, the tears of a Toby overwhelmed by the gesture, by

wanting so much to respond, to say how much that simple silent

respect said all that could or should be said in the face of

death, and from the tears Flashjack made a sea, from the sea he

made an azure sky, and into the sky, fashioned from the sunlight

in the hair of the imago standing before him, Flashjack hurled a

golden sun to light and warm Josh on his road into eternity.

*

* *

As the coffin of

polished mahogany slid slowly away through the red velvet

curtain, Josh disappearing forever into the beyond of the

crematorium, into the fire and the ash and the smoke, Flashjack

grabbed the funeral pyre and the Viking longboat and the

mausoleum and the torn lapels and the fistfuls of hair, the

whole vast stupid spectacle of grief that Toby conjured in the

Behold of his Eye, as if any monument or ritual could be

sufficient, as if any monument or ritual could even begin to

match the scale of his sorrow. And Flashjack turned the pyre

into an autumn forest of yellow, red and orange leaves; he

turned the longboat into a dragon that soared up into the sky,

its sails now wings, to swoop and soar and turn and dive and

bury itself deep in the earth, a vast reptilian power coiled

within the land, alive; he turned the mausoleum into a

palace, the palace into a city, the city into a hundred of them,

each no larger than a grain of sand, a handful of forevers which

he scattered out across the Behold to seed and grow; then, with

the hair, he stitched the torn lapels together around his own

body until he had a harlequin suit, not formed of elegant

diamonds of black and white, but rather a rough thing of rags as

rich a brown as the earth.

He turned to the

imago of Josh-who-did-not-step, Josh-before-he-died, Josh-who-did-not-die,

the Josh that Toby would now always and forever want so much and

so unattainably with a desire that made all other desires seem

as inconsequential as ash scattered to the wind; and Flashjack

bowed, beckoning along the road with a twirl of his hand.

*

* *

Epilogue

It should not be

assumed that this ending, this new beginning was, for Toby, a

moment of apotheosis which healed all wounds and banished all

horrors. There were many bleak times in the years of

Flashjack's journey with Josh into the wilds of the Behold,

times when the old darkness would rise again in other forms, and

fires would burn in the cities of the Behold. Although it was

impossible for Toby to deny the crystal clarity of his yearning

for an endless summer day of azure sky and golden sun and green

fields in which his brother still lived, although from this

imago whole fields of illusion sprang under Flashjack's dancing

feet, filling the Behold of the Eye with new wonders, and

although, somewhere along the long and winding road, it became

clear that many of the imagos now popping into existence daily

were clearly reflections of Toby's own appetence rather than

grave goods for his lost brother (the shepherds fucking in the

meadows were more than enough evidence of that, Flashjack

thought), still, sometimes the wind would carry smoke and ash,

and sometimes, when the storms rose, there would be a deep

crimson tint to the clouds, a hint of blood and fire; and

Flashjack would raise his eyes to the heavens, hoping not to see

a falling corpse. It took Toby many years to learn to cherish

life again.

*

* *

But when he did,

as he did, Flashjack was amazed at the vibrancy of the boy's

reborn desire. It wasn't that the imagos it created were grand

and exciting, wild worlds of adventure. If anything, many of

them were so subtle that Flashjack nearly missed them: the swirl

of grass in a field blown by the wind, the delicate streaks of

stratocirrus in the sky; the way an orange streetlight on

sandstone at night could give a building a rich solidity, like

in some old master's oil painting. But all these imagos,

Flashjack understood, spoke of an appetence that craved reality,

that relished life, a passion for the fragile moments of beauty

that might pass unnoticed if one were not, like Toby it seemed,

all too aware of how ephemeral they were. So he knew that a

change had taken place. It was only when Flashjack found the

teddy bear lying in the field of long grass, however, that he

truly realised how deep this change had been. The bear was

smaller, and it didn't dancedidn't move at alljust a

normal, everyday teddy bear, slightly tatty, but there was no

mistaking this imago of an appetence out of lost childhood.

There was no mistaking the bear, and there was no mistaking the

darkness in his eyes, empty of rage now, empty of hate, not a

darkness of lost hope but a darkness of quiet sorrow.

"I remember

that," said Josh. "It was his. Fuzzy."

His tiny hand

reached out to pluck the bear from Flashjack's grasp.

"I'll take it

back to him," the little boy said.

He turned and

began running across the field, head no higher than the grass.

Flashjack took a step after the child, smiling to himself as he

thought of the Grand Quest he could make of this, but a voice,

low and resonant in his ear, brought him to a halt.

Let him go

,

said the wind in the grass, the emptiness that was, perhaps,

Flashjack thought, the real spirit of the Behold. Let him go,

it said. I'll look after him from here. He wants me to. Go

home.

Flashjack nodded,

but he stood for a long while, watching the boy disappear into

the grass, bear in hand, before he turned to leave.

*

* *

It was years since

he'd last stood looking out of the window of Toby's Eye, and

with the healing of the boy's desire Flashjack was curious to

see what new marvels he might find back where it had all begun.

So what did he find there? Well, perhaps, in keeping with the

most noticeable effect of that transformation, we should phrase

it like this: What should he find there, but another faery!

Why, there he was, sitting on the branch of an apple tree,

sipping wine of the very richest red and smoking what can only

be described as the Perfect Joint, rolled so straight and so

smooth it seemed a veritable masterpiece. Batting his

iridescent wings in the wind, picking dirt out from under his

fingernails with his little kid-horns, or scratching and

scruffling his green tousle of hair, he seemed quite at home

"Who the fuck

are you?" said Flashjack. "Where did you come from?"

"A'right there,"

said the other faery. "I'm Puckerscruff. I'm a faery. You're a

lust-object imago, right? Not bad, not bad at all. Taste

and imagination; I knew I'd picked the right Beholder.

Fancy a toke?"

"Wait a minute.

I'm the bloody faery here," said Flashjack. "This is my

Behold. Go find your own sodding Behold."

"Pull the other

one, mate. Where's your wings?"

Flashjack's wings

popped out on his back in a fit of pique as he crossed his

arms. Puckerscruff looked surprised, then suspicious, then

worried, then guilty.

"Look, mate,

there wasn't a twinkle. I checked and there wasn't a twinkle.

He was looking to Beholden someone, itching to,

bursting to, and my hoary old tart was boring me towards

self-lobotomy, so I was on the lookout for new digs, and this

place seemed empty, see, so I thought, well, I can put on a

little show just on the off-chance, while they're gazing into

each other's eyes and doing the old tongue tango, right, and . .

. and . . . hey, don't look at me like that. If he hadn't been

looking for a faery, I wouldn't be here, would I? Seems to

me like someone must have been neglecting his duties.

Too busy making whoopee with the porn imagos, eh? Sorry,

OK, OK, I take that back. I didn't mean it. It's

just . . . please . . .

don't make me go back. He's a fucking label queen, all fashion

and no style, imagination of a seagull, does my fucking nut in.

You and me, mate, you and me, we'll be a team, a twosome, a

dynamic duo. I'll show you tricks you never dreamed of, mate."

All through this

speech Flashjack had been gradually advancing on Puckerscruff

who had been backing away, hands raised placatingly, but at this

last sentence Flashjack stopped. Through the window, he could

see, Toby was looking down over the sweep of his own chest and

stomach towards the head bobbing up and down at his groin.

"What kind of

tricks?" said Flashjack.

So Puckerscruff

showed him.

*

* *

It should not be

assumed that this ending, this new beginning was, for any of the

parties involved, a moment of cathartic release in which sexual

identity was affirmed and all insecurity banished. For Toby it

was by no means the first time and it was by no means the last

step. For Flashjack it was one of the most spectacular

experiences he'd ever known, but not quite, he claimed rather

tactlessly, as good as when he did it. For Puckerscruff

it was merely one in a long line of sexual adventures, and while

Flashjack was a definite looker, he was a barely competent

lover, clearly in need, Puckerscruff thought, of some good solid

training.

So the Behold of

the Eye was not transformed in an instant to utopian bliss. The

rains of shattered albums, storms of semi-molten mixing decks

and exploding glitterballs that followed most of Toby's

explorations of the gay scene were, as far as Flashjack was

concerned, a complete pain. He feltand would say so loudly

and repeatedlythat if Toby wanted to get laid so bad but

found the clubs such a bloody agonising ordeal then Toby should

just go to the bloody park at night and look tasty in the

trees. In truth, he was worriedthough he did not say this

at allthat Toby didn't do the cruising thing because

he was, on some level, still uncomfortable with his sexuality.

Puckerscruff on the other hand, who had been horrified by his

old Beholder's lack of musical taste, and who now revelled in

Toby's imago of an ideal record collection, would bounce through

these storms, fists flying, punching and head-butting the debris

as it rained down, singing Anarchy In The UK at the top

of his lungs.

It also has to be

said that Flashjack and Puckerscruff were, as his laternal

grandsister (adopted), Pebbleskip, had once warned Flashjack,

not always the most tranquil of couples, with the result that

more than a few arguments ended with the Behold divided in two

as your half and my half. And what with two

faeries in the Behold of his Eye rather than one, as Pebbleskip

had also once warned, Toby's passions did at times tend to the

intense, the glint in his eye more a fireworks display than a

twinkle; Flashjack and Puckerscruff could see it in the way he

drank and smoked, and partied and painted . . . and always with

gusto. But Pebbleskip's talk of glory and truth, angels and

demons was long since forgotten, so it was something of a

surprise when the invasion came, though not too much of a

surprise given the hallucinogen Toby had dropped a few hours

before and the fact that Flashjack and Puckerscruff were now

having a rare old time outside, whirling and twirling as they

performed Flashjack's updated, two-man Dance of the Killer

Butterfly to Toby's great amusement, his idea of the

boundary between real and imagined being rather relaxed right

now. It was Puckerscruff who noticed the demons crawling out of

a corner of the room, first one, then another, then more, very

soon a whole host of them, and angels too.

"Yeah, right," he

said. "Not a chance, mate. You lot can just fuck off."

Then he and

Flashjack began a variation of the Dance of the Killer

Butterfly, this time aimed in the general direction of the

angels and demons, with a little extra jazz hands. By the time

it was over so was the invasion, the inventions of visionary

rapture fluttering up into the air on their iridescent wings,

every one of them reborn in a pirouette of pure whimsy.

"That's a damn

sight better," said Toby.

About the Author:

Hal Duncan was

born in 1971, brought up in a small town in Ayrshire, and now

lives in the West End of Glasgow. A member of the Glasgow SF

Writers Circle, his first novel, Vellum, won the Spectrum

Award and was nominated for the Crawford, the BFS Award and the

World Fantasy Award. The sequel, Ink, came out last

year, while a novella, Escape from Hell! is due out in

2008 from Monkeybrain Books. As well as publishing a poetry

collection, Sonnets for Orpheus, he collaborated with

Scottish band Aereogramme on a song for the Ballads of the

Book album from Chemikal Underground, and has had short

fiction published in magazines such as Fantasy,

Strange Horizons and Interzone and anthologies such

as Nova Scotia, Eidolon and Logorrhea.

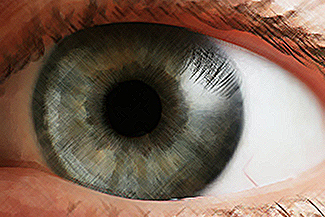

Story © 2008 Alasdair Duncan. Photo by

Petr Novák, 2005.

|