|

|

The Great Conviction of Tia

Inez

by M. Thomas

Tia Inez once beat the ghost of our

grandfather at checkers. She did this to bring Tio Roberto

back. You won’t remember it. You were very little then, and

you never paid attention to the important things.

We don't know why

Grandfather came to haunt

our porch in the States. He died in Mexico, and nobody cried

for him because he was a bastard. Sometimes Mom said to Tia

Inez, "Maybe he is trying to tell us about Roberto." She

usually said this after you’d gone to bed, and I was hiding

around the corner, listening.

We stopped going to the truck stop down south

on Saturdays, because we heard about an old, abandoned gas

station farther outside the city where the men waited for work.

Little Blanca told us about that place. She said her brother

told her he’d once seen Tio Roberto there. There, they weren’t

as likely to be bothered by police asking for green cards. But

there was no electricity or plumbing.

The men sat in the back offices on old crates

and blankets, going in and out through a broken door, waiting

for the construction bosses to need more workers. They played

cards, and drank those big milk jugs of water all day. They

peed outside, where bullnettle crept up to the edges of the

building with its razor-leaves and big, white, stinging blooms.

That summer they sweated in the airless room, and stank and

smoked, and learned to recognize us. They were teachers and a

man who had owned a shop, a pharmacist and husbands and

brothers. One man was an artist, and when he got bored he

twisted all the old wire shelves into animal shapes in the back

lot, then tried to get the bullnettle to grow on them like those

ones at Disneyland. They liked to teach you card games. They

asked us to mail letters for them, counted quarters out of their

pockets for stamps.

But they did not know about our

tio.

One day we came, and there weren’t very many

of them. We’d noticed their numbers growing fewer. A man named

Jorge followed us out to our car. He fidgeted with his cuffs

and tugged on his shirt buttons, like this. I didn’t like him.

“I seen that guy,” he said. “Couple weeks

ago near El Paso. We shared a hotel room, working construction

up there. He said he’d been in California before that for a

long time, and needed to get home. He left with a pocket full

of money, but he was sick. Nail went through the bottom of his

boot, his whole leg was red. When I first came here, I asked

about him. Some people said he’d made it back.”

Tia Inez said, “He did? He made it back?”

Jorge nodded. “You know why nobody hangs

around the old truck stop no more? Lotsa guys weren’t coming

back. They got in these cars. Not construction trucks. Nice

cars, small, with air conditioning. Big pay, lots of money.

They say, those people in the cars, it’s for construction. But

I never seen a boss drive up in an air conditioned car.”

“Inez,” Mom said, hurrying you into the back

seat. “Inez, let’s go. He doesn’t know anything.”

But Tia Inez was frozen there, listening to

Jorge, and so was I. You squished your face up against the door

window and rolled your eyes at me, but I ignored you. You were

like that a lot back then.

“They don’t come back,” Jorge said. “The

bosses tell them they have to take a health test first.” He

shrugged. “Who’s going to say no to a free check up?”

Mom started the car. “Inez, come on!”

“Where do they go?” Tia Inez asked.

Mom gunned the motor then, and I couldn’t

hear what Jorge said. You reached out and yanked at my arm, so

I slid in beside you. Sometimes you were afraid Mom would drive

off without me. I saw Tia Inez’s hand go to her mouth. Then

she ran from Jorge, slipped into the car, and slammed the door

shut.

Mom said, “You shouldn’t have listened to

him.”

Tia Inez said, “You knew about this before

and didn’t tell me.”

They didn’t talk for the rest of the ride.

* * *

Tia Inez believed her husband was alive somewhere

in the States. She missed Tio Roberto so much she paid a coyote

to get her through the desert to come looking for him, after

he’d been missing two months. When you were little, you thought

it was a real coyote, like the one on cartoons. Those scars on

her leg are from when she ran into a cholla cactus in the dark

and didn’t get all the thorns out. When she got here, she put

Tio Roberto’s picture up on the fireplace. You didn’t notice

that either, how his picture covered up Dad’s. Mom said we

should put somebody’s picture up who might actually come back.

You know, each night Tia Inez still looks at his big face and

says, "Berto, tell me where you are, and I will come to you." I

guess if you can cross the desert with a leg full of cactus

needles and two jugs of water in the middle of the night, you

figure you can go anywhere.

When we were really small

(I know you don’t

remember this) and visited Mexico at Christmas, Tio Roberto

would take me and you into the bedroom where he and Tia Inez kept

a box full of coins and bills, which they were saving for us.

Saving Mexican coins for our United States education, because

they had no children of their own. We would count them for

hours, and make stacks of them, and small villages on the floor,

and think we were going to be rich someday. Tio Roberto would

tell me, "Listen, Celia, you study hard. To get a United States

college degree would be best, so that you have something to

defend yourself with in this life."

When she came looking for him, after there

was no work in their town and Tio Roberto came to do day labor

in the States, Tia Inez brought all the coins with her that the

coyote didn’t take. Mom didn't say, but it was only enough for

half a month’s rent and a few tanks of gas to get them back and

forth to the hotel where they cleaned rooms, before Mom got the

nice job at the Wag-A-Bag.

Every Saturday we went together, three women

and one small, pesky boy, to the truck stop. We showed his

picture. "Have you seen him? He used to wait for work here."

But the men shook their heads.

Tia Inez weathered it all very well, until

the ghost of her father showed up. This was some time when you

were six, I think. Then she became furious, especially when Mom

said maybe he was there to tell us about Roberto being dead.

She would stand on the porch watching his shade slip in and out

of the dusk, glaring at him as he waved to people on the

sidewalk.

He only showed up just before night, and he

brought his own checkerboard with him. He made no sound, and

you could move the checkers with your fingers, but not feel

them. Your fingers would come away moist and cold, smelling of

mold. You remember that? He tried to spank you once, when you

made him angry, but he couldn’t touch you. Your britches came

away with wet hand prints on them. I don’t know why wet. No,

he didn’t drown. Maybe that’s just how ghosts are.

After a while Tia Inez forbade us from playing

checkers with him, and she tried to make him move to the back

porch, but he wouldn’t go. She even got the next-door neighbor Remedios to come and make one of her special recipes for feeding

the reluctant dead. Grandfather ate all the spirit mole she

made for him, then jumped two of Remedios’ checkers. Remedios

shrugged. “Sometimes, just feeding them isn’t enough,” she

said. “The dead don’t always keep themselves here.”

I don’t know what Remedios puts in the mole

for the dead. She won’t let anyone taste it.

* * *

I got up in the middle of the night because a

sound kept nagging at me. Tia Inez wasn’t in her bed, in the

room we shared. I crept up to the door, opened just a crack,

and saw candles glowing in the living room. Tia Inez and Mom

were at the table, and they had big, black shadow-grooves on

their faces that were their wrinkles, both of them no older than

I am now.

“It’s a stupid story,” Mom said. “It’s been

going around for months. They tell it to scare each other.”

“You should have told me,” Tia Inez said.

“Why? You need one more horror story to add

to your life? Crossing the desert wasn’t enough? Your missing

husband? You clean hotel rooms and have to worry someday

they’ll send you back, and it’s not enough?” Mom said.

“But the cars,” Tia Inez said. “If we could

see one of the cars. We could read the license plate. Find out

where they go, who they are–“

”And who would care?” Mom said. “Who would

you go to, Inez, who would say, ‘Oh, yes, we’ll look into that

for you, mysterious cars picking up Mexicans. Yes, we’ll find

your husband, because we care that much.’”

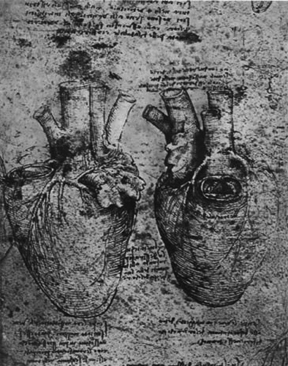

Tia Inez grabbed her hand. “He was so

strong. He had good lungs, that he laughed with. His stomach –

he could eat anything. He never drank, so it was a good liver.

He had such a good heart. A strong heart, so big, enough room

for everyone, he used to say. Who wouldn’t want his heart?”

Then she started crying again, quietly into her own hand so you

and I wouldn’t hear, nearly strangling herself with her enormous

grief.

“Inez, listen

to me,” Mom said. “If Roberto is still alive, then he is

somewhere far away, working. But if he’s dead – no, listen

– if he’s dead, and Papa’s come back to tell us that, then he’s

been stabbed or shot somewhere for his money, or couldn’t get

help for his leg, not had his body parts sold. And we will

never find him. And you have to accept that.”

But she could not. Tia Inez’s conviction was

stronger than Mom’s reality. It always has been.

* * *

That was when she began to watch cars. At

the truckstops, at the gas station, outside our house. She and

I sat on the porch in the evenings, ignoring Grandfather, who

played checkers for us and always won.

“That one,” she’d say, pointing to a shiny

new Mazda passing by. “That one’s gone around twice. You

see?” She had a great fear of nice cars back then. Still does.

When she showed Tio Roberto’s picture around,

she would say, “He might have gotten in a car. A nice one, with

air conditioning and tinted windows.”

“Lady,” one of the men said. “Nobody gets in

those kinds of cars.”

“Have you seen one?” she asked.

“Oh, sure,” he said. “I got a big fancy one

at home. I keep it in the garage of my mansion.” And he and

the other men chuckled, and sweated, and smoked, and waited for

work, and pissed out the back door on the wire animals the

artist had made.

“I had a dream, Celia,” she’d tell me, when

we were alone. She’d begun talking to me more and more, Mom

less and less. “I dreamed I was lying on a table, with a big

light over me. A man came and cut me open, here.” She drew a

line down the front of her chest. “He pulled back my skin. He

took out my stomach and put it in a dish. He took out my heart

and weighed it, like in one of the scales at the grocery store

for fruit. He said, ‘Not as good as Roberto’s.’ But he took it

anyway.”

I looked up the thing about body parts on the

school computer, but everything I read said those stories were just

legends. For a while I stopped talking to Tia Inez, because I

didn’t like hearing the story. Then I found out she was telling

the story to you, because you used to come to me in tears in the

middle of the night from nightmares. So I went back to Tia

Inez, and listened to that story over and over and over, and you

were able to get through a night by yourself again.

Jorge disappeared. Tia Inez asked about him

sometimes. Some of the men said he’d gotten in a car. But no,

it wasn’t a fancy car. Just an old pick-up.

That was when things got bad. She started

approaching hotel guests at her job. Asking them about cars,

and places where people sold body parts. Did they know where

she could get a good heart? she asked them. She had money saved

up. She needed an operation. Did they know anyone who could

get her a heart, without having to go through a hospital? Maybe

a heart you could buy from someone else?

The hotel guests complained, and they fired

her, and she sat on the porch all day, watching cars.

Then one night, she played checkers with

Grandfather. You and Mom were out somewhere. I was alone, and

I found her on the front porch, huddled over the board. She was

talking to Grandfather. I watched from inside the screen door.

“I had the dream again,” she told him. “They

took out my intestines, attached them to a lightbulb, plugged

them into the socket, and the light came on. The man cutting me

open said, ‘You know why Roberto won’t come back? Because your

bastard father is keeping him away. He got no right to that

soul he haunts your porch with. That’s Roberto’s soul he’s

borrowing.’”

She moved her red checker forward a space.

She had fewer pieces than he did. Grandfather had his eyes

narrowed, studying the board, tapping one hazy finger against

his chin, thinking.

“You listen to me, you old bastard,” she

said. “You listen to me. You never once gave thanks to God

your whole life, not for Mom, not for your children, not for

nothing good that ever happened to you. Now you want to come

back here and sit between worlds like you have the right to a

soul?”

He jumped one of her last two checkers. Now

she only had one left, but it was a king.

She took her last piece and jumped. One,

two, three, four, five times. She jumped all Grandfather’s last

checkers, she jumped from black squares to red, and when she was

finished she kept slamming her king down on the squares of the

board, one after the other, faster and faster. Grandfather got

angry, and jumped up and down, but neither he nor the checkers

made any noise.

Then he stood very still, staring at her. He

took his hand, reached into his stomach, and yanked out his

intestines. Tia Inez made this sound, this little sound, but

she didn’t move. I think I started to cry. Grandfather waggled

those intestines in front of her, and grinned, and stuck out his

tongue and danced around. He put them around his neck like a

shawl, and they dripped on his shirt. He reached back inside

himself, and ripped out his liver. There was no noise, but you

could see all the meaty parts of him straining, then snapping

away. That part he just threw over his shoulder, and it

disappeared off the edge of the porch. Then he grabbed his

chest with both hands, ripped it open, and spread his ribs so

they tore out of his skin and stuck out the sides and some fell

out on the checkerboard. He took out his heart, but it was Tio

Roberto’s face, all twisted up, slick and purple in the dusk.

That part he ate, little by little, Tio

Roberto’s eyes and nose and big, broad chin.

Tia Inez didn’t move, and I knew then that

her conviction was stronger than any I had. She faced down her

father and said, “That is my husband’s soul, and you don’t get

to keep it anymore.”

Finally, he turned away from her and went

down the porch stairs still wearing his lumpy intestines around

his neck, fading little by little into the dusk until, near the

end of the sidewalk, he was gone.

Tia Inez turned and saw me watching from

behind the screen door. She held up her hands, and water

dripped from them, from the checkers. She said, “You’ll see,

Celia. Now Roberto will come back.” From that day forward

she’s sat on the porch morning to night, counting fancy cars,

waiting for Tio Roberto. Grandfather never returned. I’m

telling you, she does it every day, even when you’re not here.

Look, things don’t stop happening just because you’re away at

grad school.

No, I didn’t sign up for those night classes

with the money you sent. Mom needed to have a tooth pulled. I

already told you what Tia Inez does out on the porch all day.

She plays checkers with herself and scratches her cholla scars

and waits for Tio Roberto.

Every now and then I have a dream about

watching some men take out your insides and weigh them. Don’t

laugh. I don’t have anybody to run to at night, so that’s why I

call a lot, just to make sure. Tio Roberto was a nice guy. You

would have liked him, and he would have been proud of you.

Okay, sure, I’m proud of you too.

Sometimes, in that dream, I’m one of the

people taking out your insides. I always get to weigh your

heart. And in the dream I say, “This one is heavy. It can

defend us all.”

About the Author:

M. Thomas is an

author and teacher in Texas. Her work has appeared in Strange

Horizons, OnSpec, and Fantasy magazine, among others.

She is currently a fiction editor for Chiaroscuro ezine. You can

visit her website here.

Story © 2006 M. Thomas.

|