|

|

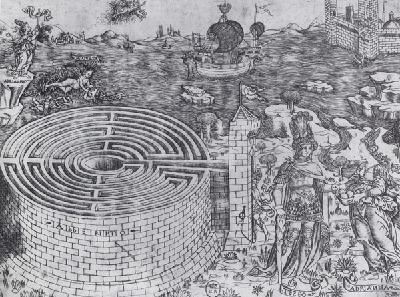

Thread: A Triptych

by Catherynne M.

Valente

For Phanitzia Barakaras

I came, I

came out of the red dirt of Heraklion like a golem licking dust

from its finger-webbing; I came because he called me, he told me

to come, he wrote my name on a crisp white form and I stepped

over the water, over the purple foam, over the breakers like

dogs’ tails, I came with my feet still smelling of Cretan sand.

He ordered

me like a suit: black hair, black eyes, slim hips, breasts fit

to feed sons. Good blood, of course; he paid extra for the

pedigree, for the fine nasal bones and the high chin that just

would not sink into the chest, no matter how many rubbed-smooth

coins passed under it for the purchase of a womb. Dress her

up, he wrote to my mother, I won’t have my bride wander

on the ship’s decks in peasant filth. And she dressed me,

first of my siblings to be sold: a wide red belt and black

stockings like sackcloth. And she put the spindle into my hands,

bulging with thread, with yarn, for my baby’s clothes, for

surely he’d get me with child before he got me home from

harbor.

She patted

my cheek.

The lines

on her face were long and thin as the bristles of a

bull.

The ship

was so white, tablecloths covering wood like snow over stones,

and all the silver, all the wax candles, all the delicate piles

of carrot and leek, bright as sacrifices on the spotless plates.

He made sure I was kept above the rabble, in the white and pure

parts of the ship—his woman from the old country would arrive

stunned and humbled by his wealth. And yet it all stank of sweat

and fat flesh, it all stank of women’s blood and stale whiskey,

it all stank under the talcum and white. And I said nothing

while the ship crossed the sea, the wine-dark sea, I said

nothing through the three-week crossing, as though I was doing

penance, as though I were a nun cast into the desert to starve

into holiness. I spoke to no one until the man in the brass

buttons stood behind his teak vestibule and recorded my name in

his book as “Annie Smith.”

Eipa

Ariadne, I

whispered, kathariste ta autia sas.

But he

wrote me down as Annie anyway, wrote me in his great black book

which must be a book of the dead, and he Charon on a raft of red

wood, with a punting pole of ink, and he wrote my name in his

book, he wrote my name among the other dead women crossing over

the water, and I was Annie and not Ariadne, I was Annie now and

some broad-shouldered man’s wife in a city called Chicago, and

not Ariadne at all.

*

* *

His house

was white, white and stone, and in it I stood like a smear,

black on black, and my red belt gleaming. He had lemon-cake and

black tea waiting. He looked at my teeth. He wanted a woman from

home, he explained, as though it made perfect sense, one who

would not trade an honest broom for gin. He pinched my cheek to

see the color; he showed me clothes which were neither coarse

nor black, lined up shoulder to shoulder like churchgoers.

“Give me

that old thread, Annie,” he said kindly, “it is Annie, isn’t it?

I will have a woman downtown make you a nice Sunday dress.”

I clutched

my wad of scarlet to my chest, bright as a heart. “Annie,” I

answered slowly, pulling words like beads from my own mouth, “my

name is Annie, yes, but you cannot have my thread. It is for my

baby, when it comes.”

He

shrugged. It didn’t matter. Thread is nothing to a man, it is

string, it is knots.

He let me

finish the delicately iced cake before he took the rough-woven

dress from my shoulders, before he took the wide red belt from

my waist, and where there was no dress nor belt there were red

lines from the rough fabric, red lines from the tightened sash:

I wore the belt on my flesh long after the thing was gone from

me.

Annie,

he panted, and opened my legs on a long yellow couch before a

cold furnace. The light slanted in like slabs of cake, and the

room was full of sick and sweet—Annie, you smell like

Heraklion, you smell like red dust and bullhide, you smell like

old walls spiraling in and in and in, oh, Annie, you spiral in—

I put my

arms around him, shyly, tentative as a girl my age ought to be,

and he rocked over me like a pendulum, and I watched my hair

fall down between us, and I whispered as he cried a son into me,

whispered as the couch creaked beneath me:

Theseus,

oh, Theseus. Don’t you know me? Won’t you say my name? What

Cretan girl was ever called Annie?

He choked

and the son spilled out of him, and I could feel little black

eyes shuddering in me, and the light slanted still, and the

clock hushed out the day.

He showed

me the kitchen, and asked for coffee at eight.

When the

boy was born, his cow-eyes blinked limpid up at me, and his hair

was coarse as my dress, coarse as the tail of a bull. I rolled

out my thread and rocked his crib with my foot; I rolled out my

crimson thread, the thread that tumbled from me to him, a little

path across the rug-strewn floor. I embroidered his little

jacket and trousers with red flowers, red castles, red cows

chewing cud in a red field. I embroidered old walls; I sewed

seven youths and seven maidens; I pulled my needle through and

through, and up came a red maze across the shoulders, and a thin

path between its angles.

My son

cried, and my body tightened, swollen with milk. The light

slanted in like fingers, and the thread stuck in his sweaty

scalp as he drank, gurgling, greedy.

In two

months I was pregnant again, but I had no thread left for this

second son, this other boy whose limbs were fat and pink, who

had ten toes and ten fingers, and who wore the jacket when his

brother grew out of it, but the trousers never fit right, never

fit over his plump little legs, legs which emerged from me

already downed in dark hair.

He looked

at me when they put the second child to my breast, looked at me

sidelong, thoughtful, as if calculating a sum. He kissed my

forehead and whispered, “What a good girl you are, Annie. What a

good, sweet girl.”

*

* *

The man in

the brass buttons stood behind his teak vestibule and recorded

my name in his books.

Annie

Smith.

He

listened to my husband politely, and recorded his answers like

names. Like names, yes, he invoked them solemnly, pantheon-names

to be blazoned over my brow, fixed to my wrists,

neurasthenic-gods thrown up into star-graves, constellations,

networks of names which were not mine, but were strapped to me,

corkscrewed into me. Annie-not-Ariadne, Chicago-not-Heraklion,

post-partum schizoid break, anhedonia. But I knew the truth of

it, I knew there was a woman waiting in his sleek black car, a

woman with pale hair who did not smell of red dust and Heraklion,

who had no gum-marks on her rosy breasts.

I bent my

head and let them read out my new names just the same. Only once

did I look up at him, did I make my eyes huge and pleading, did

I murmur: Parakalo. Parakalo me parte spiti.

He rolled

his eyes. He rolled his eyes and a new name was added:

Defiant. Refuses to speak English. He rolled his eyes and

left me with the man in the brass buttons, and my sons toddled

after him, one in each hand. The younger one had outgrown his

jacket, and his brown wrists stuck through the tight sleeves.

His little shoes squeaked on the white floor, and the man in the

brass buttons closed a cool hand over my shoulder.

It is cool

in these hundred rooms, cool as stones, cool as shoals. He left

me here. He did not want me. He left me here and they put a

needle in the shallow of my elbow and I slept, and I woke up in

the water, oh, the water was lapping my toes, my fists, foaming

between fingers like wicked white whispering tongues, like

sheet-corners torn loose. My hair floated damp around me; a ruin

of conch scoured my back. He did not want me and I woke up in

the water—I woke up in the water and the sky was blank, blank

and so close. It is cool in these hundred rooms and the walls

are blank, the air-conditioners like zephyrs, and there are

anemone waving in my veins, red and green, red and green, and

everywhere I look the strand continues on, this bleak island

without a single tree, with only conch-corpses grinding away at

the tide to hammer at the silence.

He did not

want me, and I woke up in the water.

I woke up

with the thread tangled over my limbs, broken and splattered,

thread spooling out of my navel, out of the labyrinth that was

me, the fallopian-whorl that succored a hairy child whose head

was too large, and another who snorted while he slept. He walked

into me on a red thread, and I was always the labyrinth, the

only labyrinth, and the thread wandered through me with a

goat-grin, and saw the Minotaur inside me, saw my brother, or my

sons, I cannot tell anymore—look, they all have horns! Yes,

horned men all, and my mother strapped into the cattle-machine,

still screaming, still screaming, and all of them rooted in me,

in my stomach, in me strapped into the thunder-machine, still

screaming, still screaming, and they are all marching into me

and out again, their boots on my bones are like syringes,

plunging in and out and flooding me with morphine-minotaurs,

gold-electric, thorazine-thread, flooding, flooding—he did not

want me, Theseus did not want me, he wanted the bull-sons, and I

woke up, I woke up, I woke up in the water.

I tried to

follow it back out, out of myself, out of the miasma of flesh

that these hundred rooms have made of me, maze within maze,

woman within maze—and Annie is gone, fled, Ariadne is left, and

she is the maze and she is in the maze, she is lost in the white

and the water, and her cow-children are not playing in the surf

but she can hear them lowing, she can hear them and Theseus

trampling the kelp. I cannot follow the thread; it keeps coming

out of me, like blood, like placenta, and it is all over my

hands, and I cannot get it off, I cannot get it off—please, I

don’t want any of that. I don’t want it; it maketh me to lie

down in green pastures, it maketh me to lie under the too-close

sky, it maketh me to lie down on the grey beach and the thread

keeps coming out of me—ravel, unravel, ravel, ravel again—the

sky is coming open at the edges—I don’t want any of that,

please, it makes me so sick.

He left me

here, and, in Scythia, Hippolyta is holding a brand to her

severed breast.

The sky,

the sky too-close, and there are unraveled clouds watching me,

watching my feet in the sand, and they are coming down to me,

they saw me, they spied me with their moon-born eye, and they

are coming down, and they are the grape-spoked wheels of a

chariot, and a fennel-whip slaps the grey flanks of cloud-mares,

and a black beard blots out the sun and let me up—oh, please,

take these things off me—he is coming and I cannot get away,

tied to a bed, tied to a beach, he is coming and he smells of

sweat and sons. He wants to fill me up with it, Dionysus out of

the clouds, to fill me up with him, with glass phials full of

catskin and grapes, phials full of wine-dark sea, phials of

sleep and somber. He wants to hold me under the tide and tell me

I will get better, I will get better, I will get well if I let

him help me. He wants to put me in the machine and make me the

vine-god’s Pasiphaë, push all those leaves and roots into me,

into the monster-making labyrinth, and when he is finished wine

will gush out of me like an arterial spray, and he will lap it

up, oh, he will gurgle and slurp at me—

Theseus

did not want me, and in Knossos Phaedra is brushing her black

hair.

I’m so

thirsty, and the sea is full of salt. I can hear his wheels on

the conch-shatter; I can hear his feet in the hundred rooms—when

can I see my sons again?—I can hear him calling my name and with

fennel on his breath he never calls me Annie, but I don’t want

him, I don’t want to be a labyrinth, I don’t want to smell of

bulls and bronze and bactine, I just want to walk into the sea

and let it cover my head, I just want to clutch my thread to my

chest and walk past the breakers, but his beard is so black, and

he holds my hips with hands of grass, and his cries are full

trumpeted ioioioio, his voice is a spurt of wine,

ioioioio, and he is violet and sour, so sour, and so close.

I cry and

he does not care. The cats howl and the thyrsoi rattle and the

grapes burst all around, but he does not stop, he never stops,

and when will I see my boys again? Where are my boys? I am their

mother, why don’t they come?

He left me

here and sailed away under black sails and I woke up in the

water, in the water, and I have forgotten what the roofs of

Heraklion looked like, whether they were white or red. Every

night I am swollen up with wine, and every morning I am drained

again, and the conches are crushed beneath my back as he leaps

onto me—please. Please. I don’t want any of that. I’ll be good;

I’ll be quiet. I’ll wake up in the quiet water and be a quiet

girl, and when my boys come to see me tell them how quiet I was,

how good and sweet—and when the vine-god came I didn’t say no,

because Cretan girls know their place.

About the Author:

Catherynne M. Valente’s work

in poetry and short fiction can be found online and in print in such journals as

The Pedestal Magazine, Fantastic Metropolis, The Women's Arts

Network, NYC Big City Lit, Jabberwocky, Mythic Delirium,

Fantasy Magazine, forthcoming issues of Electric Velocipede,

Cabinet des Fees, and Star*Line, and anthologies such as The Book

of Voices (benefiting Sierra Leone PEN), The Minotaur in Pamplona,

and The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror #18. She has authored a chapbook,

Music of a Proto-Suicide, the novels The Labyrinth and Yume no

Hon: The Book of Dreams, and two collections of poetry, Apocrypha and

Oracles. Forthcoming works include novels The Grass-Cutting Sword

and The Ice Puzzle, as well as her first major fantasy series The

Orphan's Tales, which will be published by Bantam/Dell in 2006. She

currently lives in Virginia with her beloved husband and two high-maintenance

dogs, having recently returned from a long residence in Japan.

Story © 2006 Catherynne M. Valente.

|