A Lock of Ra

by Sandra McDonald

The supermarket shelves

had little on

them, and the produce bins held only moldy tomatoes and some shriveled

cucumbers. Ann bought all that she could, paying more than twice what she

would have just a month ago, and drove through the mostly empty streets of Cloquet, Minnesota to her mother's small house. The neighborhood was quiet

in the gloomy afternoon light, all the summer gardens withered from

neglect.

"Sweetheart, why did you bother?" Mary asked

when she opened the door. "It's too much for just little me."

Ann carried a box of canned vegetables and

soups to the kitchen table. "I had to, Mom. I don't know when I'll be

back."

The television on the counter displayed the

face of an anxious newscaster. Ann stared at him, wondering which crisis

had risen to the forefront. Mary used her remote to turn off the screen.

Mary said, "Never you mind about what's

going on out there. Lindsay's all you have to worry about."

"And you." Ann started putting the cans away

and nearly snagged her wedding ring on the side of the box. "I wish you'd

come to Rochester with me."

Mary shuffled to the kitchen sink and

reached for a bottle of yellow pills. "This is where I was born and this is

where I'm staying. John Fritz across the street promised to keep an eye

out. He's got two shotguns and a pistol. It's Daniel who should be with

the two of you, and not hiding behind his desk."

"He's not hiding," Ann said, hating the note

of defensiveness in her voice. Daniel had been called over to Duluth

by his employers. His job was their only source of income, and they

desperately needed the medical insurance.

"Men and illness," Mary said.

"Oil and water."

Ann put away the groceries, fixed a running

toilet, and lugged three bins of trash out to the curb. The sanitation

truck had not been by in awhile, but the stench in the garage was

overwhelming. Afterward she scrubbed her hands clean and let her

mother fix her a sandwich. Ann ate it along with warm soda and stale

potato chips. Outside the kitchen window, a skinny black dog without a

collar nosed at the trash.

"Before I forget, this is for

Lindsay." Mary handed over a small piece of jewelry. " Tell her

I'm sorry about not being able to visit."

Ann took the brooch. The rim

was a smooth oval of tarnished gold. At the center of it, under

old glass, someone had embroidered a castle and tree under a

small, watchful sun. "Where did you get it?"

"From Mae Woolcott, at the

church." Mary put their dishes in the sink and gazed out the

window. "She said they're going to try down south, maybe her

son can find work there. None of them have been the same since

her granddaughter passed."

Ann squeezed the bridge of her nose.

"No one should suffer like those

children do," Mary said. "You don't say it, but I see it in your

eyes. All the little lambs."

"Don't, Mom. Don't give up

hope. If you don't have it, I don't know how I will--"

Mary turned from the window and

touched Ann's cheek. "When you don't have hope, have faith."

But Ann had little faith that

medical science could save her daughter's life, and none at all

that a higher power might deign to stop the spread of cancerous

cells in Lindsay's brain. That afternoon she returned to

Rochester on a high-speed train with the brooch in her pocket.

Skycars danced among the clouds, sleek blue craft that could

almost be mistaken for distant sparrows.

* * *

*

A riot delayed her progress into

the city. "You know things are getting bad when even Minnesotans

revolt," her father had once joked, just weeks before emphysema

shut down his lungs for the last time. Ann turned from the

train window and closed her eyes, unwilling to face anyone's

problems but her own.

When she reached the pediatric

oncology unit, pink elephants were frolicking on the walls and

singing cheerful songs. Children's laughter bubbled up from

nearby, so sweet that Ann could almost imagine herself back at

Cloquet Elementary picking Lindsay up at the end of the day.

She poked her head into the rec room and saw several of the

children being entertained by a clown in a fluorescent green

wig. The clown deftly pulled a handkerchief from his right ear,

tucked it with great fanfare into his left ear, and then

withdrew it in a long stream from one of his nostrils.

"Ewww," went the children, and

the mothers and nurses standing in the back all smiled.

The clown draped the

handkerchief on the bald head of little Tommy Norwell, whose

seventh birthday had just passed a few days earlier. Tommy

tossed it to Jeannie Belson, age five, whose face drooped

terribly on the left side.

"Oops." The clown started to

pull another handkerchief from his nose. "I forgot one!"

Ann checked the kitchen, where

the Willis twins were eating ice cream with their mother Tina.

"Lindsay's in her room," Tina

said. "I saw Dr. Anderson down there."

"Thanks," Ann said past the

tightness in her throat. She'd learned early on that doctors

made rounds early in the morning or late at night, and visits at

any other time generally meant bad news.

"Ann, if you see Rita Helsson . . . ."

Rita was one of Ann's neighbors,

and had a one-year-old daughter with the sweetest dimples Ann

had ever seen. Ann asked, "Yes?"

Tina looked at the twins, who

were absorbed in their hot fudge sundaes, and shook her head.

Ann wanted to moan. Instead she

hurried down the hall toward Lindsay's room, her footsteps muted

against the self-cleaning floor. Lindsay was sitting up in bed

with a bright scarf tied over her head. A white holographic

kitten was curled up against her side, its tail twitching from

side to side. The room's flexible décor was dialed to Princess

Mode, which meant simulated pink curtains on the picture window

and a lacey canopy draped over the bed.

Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down

your hair, Ann

thought, but Lindsay's long curls had fallen out months ago, and

no brave knight would be riding to her rescue.

"Hi, Mom," Lindsay said.

"Where's Dad?"

Dr. Anderson, the chief

pediatric oncologist, turned from the foot of the bed. He had

Lindsay's electronic chart in one hand and his personal stylus

in the other. "Mrs. Rotsvold. I'm glad you're back. This is

Dr. Qaddoumi. She's become quite an expert on Ersson's."

He wouldn't have called it that

if the Ersson company lawyers had been around. They tolerated

Cloquet Syndrome but preferred non-specified glioma.

Ann and the other mothers had taken to calling it what it really

was: that bastard cancer that's stealing our children.

Calling it what it really was didn't offer much comfort.

"Dr. Qaddoumi." Ann acknowledged

the woman standing next to Dr. Anderson and then took Lindsay's hand. "Daddy couldn't come,

honey. He had to stay at work."

Lindsay scowled and pulled her

hand away. "But he said he would! He promised!"

Dr. Anderson caught Ann's gaze

and tilted his head toward the door. "We should talk outside."

Ann didn't think she wanted to

hear what he had to say. She ignored him, just for the moment,

and sat on the edge of Lindsay's bed. "Daddy wanted to come. He

just couldn't. But he sent you this--says you don't have this

one."

Lindsay held out her hand for

the figurine of a Persian cat. No bigger than Ann's thumb, it

was made of pewter with gold plating and sported a collar of

fake diamonds. With barely a glance, Lindsay deposited it on

her side table, where a dozen other feline statues encircled the

schoolbooks she was supposed to be reading when her vision

wasn't blurry. She said, "It's not fair. He said he'd be

here."

Ann patted her shoulder, unable

to explain more about fathers who had to work while their little

girls grew sicker and sicker. She pulled out the brooch. "Oh,

and Grandma says hi, too. She sent you a present. Look how pretty

it is."

Lindsay turned her head and

wiped her nose with her hand. "I don't care."

Dr. Qaddoumi, dark-haired and

plain behind a set of old-fashioned glasses, stepped forward and

said, "That's quite a lovely piece. Victorian, isn't it?"

"I suppose," Ann said.

Lindsay darted a glance their

way. "What's 'Victorian' mean?"

Dr. Qaddoumi said, "Victoria was

the queen of England a long time ago. It was very fashionable

during her reign for people to use hair as jewelry, so that they

could remember their friends and loved ones. Hair art, they

called it."

Ann asked, "Hair? What hair?"

Dr. Qaddoumi pointed her finger.

"See the sun? Someone's fine blond hair. The tree, too."

"She's right, Mom," Lindsay said

in delight. She snatched the brooch from Ann's hand. "Whose is

it?"

"I don't know." Ann pushed down

a flicker of revulsion--a stranger's hair in her

daughter's hands--and looked at Dr. Qaddoumi. "It's okay, isn't

it?"

Dr. Qaddoumi smiled. "It's a

treasure to value. Keep it safe, Lindsay."

Dr. Anderson cleared his throat.

"Mrs. Rotsvold," he said, and again nodded toward the door.

Lindsay leaned back in the bed,

the brooch clasped tightly. The dark circles under her eyes

looked so much like smudged paint that Ann almost reached over

to wipe them away. Ann followed the doctors to the parents'

lounge, which had been painted a soft and soothing yellow. She

asked, "It's the chemotherapy, isn't it? It's not working."

Dr. Anderson twisted his stylus

between his long, slender fingers. "We did an MRI this morning."

Ann looked up at the ceiling.

She'd read that the act of looking up kept one from crying,

though in her experience it didn't work very well. "She's had

surgery, four rounds of treatment--"

"Ann," Dr. Anderson said, and it

was always bad when he used her first name. "The tumor in her

frontal lobe is back."

She clasped her hands together

and counted to five. Somewhere down the hall a baby let out a

weak cry and then fell silent. "So what's next? Radiation?"

"It's an option," Dr. Anderson

said slowly. Again he twisted the stylus. "We've talked about

the possible side-effects. Frankly, it hasn't done much good in

the handful of cases more advanced than Lindsay's. Dr. Qaddoumi

here might have an alternative."

Dr. Qaddoumi scooted closer to

the edge of her seat. "Mrs. Rotsvold, my team and I have been

working on a new generation of hypertexaphyrins designed to go

after the so-called 'super gliomas,' such as Ersson's. We've

been approved for clinical trials, and we'd like for you to

consider enrolling Lindsay. We would cover the costs, of

course--"

"You want her to be in an

experiment?" Ann asked. "Like a rat?"

"We know Ersson's is a

particularly aggressive type of brain cancer, fast-growing and

resistant to conventional therapies," Dr. Anderson said. "We

could go back into Lindsay's skull, yes. We could bombard her

with radiation. But Dr. Qaddoumi's work--"

Ann held up a hand. "I need to

know all the drawbacks. The risks. What could go right, as

well as go wrong."

"I will forward all the

information you need." Dr. Qaddoumi's eyes were wide and

unblinking behind her glasses. Ann thought she was probably

quite lovely when she took them off and let loose her hair. "I

wouldn't suggest Lindsay's participation if I didn't think she

could benefit."

It was tempting to dive right

in, to say yes to any slim chance of hope, but Ann squared her

shoulders. "And I have to talk to my husband."

Dr. Anderson tucked the stylus

into his pocket and reached for the lounge door. "I would do

that as soon as possible, if I were you."

The tone of his voice left her

little doubt that Lindsay's life depended on it.

Dr. Qaddoumi touched Ann's arm

lightly. It was so rare for a doctor to touch her that Ann's

skin tingled. Dr. Qaddoumi said, "These hypertexaphyrins are a

good thing, Mrs. Rotsvold. I will ask you to put your faith in

me and in them."

* *

* *

The Ersson Corporation

disclaimer flashed onscreen. This communication might be

monitored for compliance, it read, the words small and clear

beneath a flying car logo. Daniel appeared on the screen,

framed by bookshelves.

"How is she?" he asked.

"Mad at you," Ann answered.

"I know. When I asked Peters

for more sick leave she just gave me that 'resources are

stretched too thin' look, as if--"

Ann cut him off. "Dr. Anderson

said the tumor's back."

Daniel rolled back from the

screen. Ann wished she had the luxury to physically recoil.

The oncology unit's comm closet, dim and soundproof, was too

small for her to go anywhere.

"Ann," he murmured, and covered

his eyes.

"They want to put her into a

clinical trial," she said, and forwarded a batch of e-text for

his review. "Hypertexaphyrins. I met with the doctor in

charge."

"Is anybody else doing it? Any

other families?"

"What does it matter?"

Daniel lifted his chin. "Don't

be annoyed. I'm just saying we shouldn't be the first."

"I don't care if we're first or

last or anywhere in the middle, as long as it does what it's

supposed to." Ann dug her fingernails into her palm. "Open the

files I just sent you. They're fact sheets the doctor gave me

and some medical articles I found."

"You know I don't understand any

of that mumbo jumbo--"

She cut him off. "You're a

fucking engineer, Daniel. Read it."

He looked at something

off-screen--a person, perhaps, or a window back in Duluth, or

one of his damned tech specs, the Ersson flying car in all its

component glory.

"I'll take it with me," he said.

"I have to go to Detroit to work out some relay kinks in the

skylines. Shouldn't be more than a few days, if we get a

security escort--"

"You're going away?" she asked,

and heard the brittleness in her own voice. "Our daughter is

dying and you're taking a business trip?"

"She's not dying!" Daniel

snapped. "How can you even think that?"

They stared at each other.

"You decide," he finally said.

"Lindsay and I trust you. I'll call from Detroit."

Daniel cut the connection,

and the screen went dark.

Ann would have swept the damn

thing to the floor, but it was securely bolted to the table.

* *

* *

Texaphyrins were synthetic

compounds that targeted areas of high molecular activity, such

as cancer cells. Hypertexaphyrins were their newest evolution,

and carried risks that didn't seem worse than what Lindsay was

already facing. As Ann combed through both the supplied data

and her own research she saw that their efficacy with children

was less than it was with adults. But Dr. Qaddoumi seemed so

confident . . . perhaps it was the wrong way to make such a

monumental decision, maybe she was being too emotional and

feminine, but she trusted Qaddoumi. With the news filled

with violence and her only child failing under an onslaught of

malignancy, Ann was ready to grasp any lifeline the doctors

threw her.

"Let's go ahead," Ann said, and

signed all the required forms.

"Thank you," Dr. Qaddoumi said.

"We'll take good care of Lindsay, Mrs. Rotsvold."

Lindsay was listless the day

treatment started and began vomiting on the second, but by day

four some pink had come back into her cheeks. Though fatigued,

she started visiting the rec room again, and before Ann knew it,

she'd interested a half dozen other kids in the novelty of using

human hair in their artwork.

"It's a willow tree," Tommy

Norwell said, showing off snippets of his mother's gray hair

glued atop a drawing of a tree trunk.

"Mine's a kitty," one of the

Willis twins said, and Ann saw the whiskers and tail on the clay

sculpture were dark strands, thin and wavy.

One of the social workers

brought in a book about hair jewelry. "Look, Mom," Lindsay said,

flipping through the pages. "Bracelets and rings--and these

earrings--"

Ann studied the delicate work,

imagining how many hours had gone into twisting and braiding and

gluing. She had once saved a lock of Lindsay's baby hair, but

it had gotten lost when Daniel received his promotion and they

moved from the middle-class side of Cloquet to the upscale

neighborhood where other executives lived. "A casualty of

success," he'd joked, and she wondered if he regretted it in

retrospect now that the whole town was a casualty, its children

the most obvious victims. But Daniel was among those who

insisted that Cloquet's cancer cluster had nothing to do with

the Ersson Skycar factory or its byproducts, and that a dozen

other environmental suspects had to be investigated and discounted.

"Can I have some of your hair,

Mom?" Lindsay asked. "I'm going to make a bracelet."

Lindsay asked other mothers,

too, and then the nurses and doctors. Dr. Anderson patted his

bristle top with good humor and said he had none to spare. Dr.

Qaddoumi, doing her morning rounds, took the request more

seriously.

"When you ask for someone's

hair, you ask them to surrender some of their strength," she

said.

Ann rose from the courtesy bed

where she'd spent a sleepless night. She remembered her church

lessons. "Like Samson and Delilah?"

"I saw them on TV." Lindsay was

busy arranging her cat statues into a circle on her breakfast

tray. The brooch was at the center of the statues. "She cut off

his hair while he was sleeping. I wouldn't do that."

Dr. Qaddoumi touched Lindsay's

wrist with the tips of her fingers. "My grandmother used to tell

me the story of the goose and the sun. The sun had a full head

of hair then, glorious yellow hair, and even one tiny strand of

it could work great magic. The goose was a pleasant little

fellow who was attacked by a mean snake. The only one thing

that could save him was a lock of the sun's hair, but he was too

afraid to ask."

Lindsay asked, "Couldn't someone

ask for him? His Mom?"

"You're a very smart girl.

That's exactly what happened," Dr. Qaddoumi said. "His mother

asked. And the sun said yes. The goose made a full recovery."

"So Mother Goose saved the day,"

Ann joked, but Dr. Qaddoumi's face remained serious.

Lindsay gave Ann a beseeching

look. "You have to ask, Mom. Ask the sun to make me well."

Ann obliged. "Sun, please make

Lindsay well."

"And everyone else, too,"

Lindsay insisted, her voice high and anxious. She reached for

the brooch, accidentally knocking over some of the cats. "And

you have to say it with your hand on this, because it's like

magic."

Ann put her hand on the brooch.

"Sun, please make Lindsay and everyone else well."

Lindsay leaned back on her

pillows. Her frown lessened a little. "So can I have some of

your hair, Dr. Q?"

"I would be honored," Dr.

Qaddoumi said.

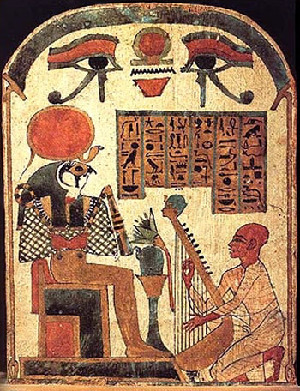

Later that day Ann looked up Dr.

Qaddoumi's story on the net and deduced that the goose was Geb,

the Egyptian god of the underworld and keeper of the dead. The

sun was the god Ra, all knowing, all mighty. She wondered what

gods Dr. Qaddoumi worshipped each night after walking among sick

and dying children. She wished prayers really did work, but

knew better. Ann settled for sitting in the rec room with the

other mothers, watching the children of Cloquet transform

ordinary human hair into pieces of art.

* *

* *

Nineteen-year-old Mallory Caine,

lithe and gorgeous, was Cloquet's best claim to fame aside from

deadly tumors. She swept onto the ward with a media crew in tow

and posed for footage with her arms around the children, who

adored her as the star of the Princess Rapunzel film series.

"If I have to watch The

Knight We Met one more time . . . ." Tina Willis murmured to

Ann, but she looked as starstruck as anyone else.

"Miss Caine," one of the

reporters said, "you lived in Cloquet until you were thirteen.

You went to the same schools these children did. Do you worry

about developing brain cancer yourself?"

Mallory tossed her shiny blonde

hair over her shoulder. "My doctors have told me I'm healthy,

and I feel blessed. But how can anyone rest easy until a cure

is found?"

Lindsay certainly wasn't resting

easy. She'd woken feverish and disoriented around midnight,

crying, "Daddy, where's Daddy? I want Daddy." Ann tried not to

be hurt even though Daniel had been dispatched to St. Paul and

hadn't called in days. The phones weren't working well, someone

had said. Dr. Qaddoumi and Dr. Anderson arrived in the wee

hours in response to the nurse's page, and though they said

nothing Ann was certain the hypertexaphyrins were failing. At

least the fever medicine seemed to be working, enough so that

Lindsay broke into a broad smile when Mallory visited her room.

"You're my favorite princess

ever," Lindsay said, and blushed. "I mean actress.

Here. This is for you. I made it out of hair. Mine and my

mom's and my doctor's--"

Mallory held up the bracelet

with a perplexed expression. "Human hair? Real hair?"

"It's Victorian," Lindsay added

in pride.

Ann stepped forward, sure that

Mallory would say something thoughtless or rude, but Mallory

surprised her by asking Lindsay how and why she had it made it.

The actress's eyes grew brighter as she learned about the

children's projects and within minutes she was asking for a pair

of scissors.

"If hair makes their days

happier," she said, dramatically sawing off a long lock in front

of the camera, "then it's the least I can do."

The next day hair started

arriving from all over the world--a few strands in one envelope,

six inches in another, hair that was curly and straight and

bright and dark, hair for the children of Cloquet. Cities were

burning in Europe, nuclear weapons were poised to fire at the

slightest provocation, but hair continued to come like peace

offerings, like tokens of surrender. Ann was touched by the

kindness, but then Dr. Anderson told her that some of the hair

was pubic hair, some had lice in it, and much of it was dirty

and gnarled.

"It's best we throw it all

away," he said.

One of the Willis twins passed

away in her sleep. The nurses closed all the doors in the unit

so the other children wouldn't see the morgue attendant come to

claim her. Ann watched the gurney roll away and thought

another innocent victim, and tried to think of something

comforting she could offer to Tina Willis. Something that

wouldn't sound stupid when her turn came, when Lindsay was the

one rolled away . . . .

"I don't think anything's

helping," Ann said to her mother in the quiet confines of the comm closet. "I think . . . I don't know what to do. I even

tried praying. Me. How's that for a laugh?"

Mary said, "Call Daniel. Tell

him to come to you. Tell him to hurry while he still has

somewhere to hurry to, you understand?"

"What's wrong?" Ann leaned

closer to the screen. "Are you all right? Is Cloquet--"

"Things can't go on as they are

much longer. I don't want you watching the news, you hear me?

There are too many rumors, too much fear. But someone's going

to make a mistake that can't be taken back. I can feel it

coming, like static electricity in the air."

"You could take the train

here--or I could come home--"

Mary smiled grimly. "Don't worry

about me. I'm not afraid of any crazy Chinese in bunkers, or

presidents who think they can bluff them. You stay there, where

you belong."

Someone knocked on the closet

door. Ann saw Dr. Qaddoumi standing outside, a worry line

between her eyes. They went to the parents' lounge, where Ann

paced and wished she could have a cigarette or drink or

sedative, anything at all to calm herself.

"It's not working," Ann said.

"She's getting weaker and sicker. Last night she couldn't even

keep her pudding down, and she loves pudding. If I thought it

was helping I'd tell you to keep going but the way she is now--"

Dr. Qaddoumi said, "Mrs.

Rotsvold, the hypertexaphyrins are doing exactly what they are

designed to do. Lindsay's primary tumor has shrunk fifty

percent since her last MRI. But now the cancer is springing up

in other parts of her body, as it has with other children. The

drugs can't keep up with them."

Ann stopped at the window, the

strength in her legs abruptly fading. A skycar drifted in from

the north, heading for the hospital's parking lot. Damn Ersson

anyway. Damn the men and women who'd made it possible to fly

toward the sun, which was perpetually hidden by smog. "She's not

going to . . . ." she started, but couldn't finish the

sentence. She cleared her throat. "You once told Lindsay a

story about Geb and Ra. Geb's mother made an appeal. Tell me

how. Tell me what to say."

"The story came from my

grandparents," Dr. Qaddoumi said. "I made up the part about the

mother."

The skycar landed, discharging a

stream of passengers. "Why?" Ann asked.

Dr. Qaddoumi smoothed the hem of

her skirt. "I had a son. He died in the San Francisco

explosions three years ago, along with his father."

"Oh." Ann tried to think of something more

sympathetic to say, but her mind went blank.

Dr. Qaddoumi stared down at her

knees. "I thought, afterward, that I should have been a more

devout woman, that I should have prayed to any and every god to

keep my family safe. You have to ask for the things you want in

this world, not expect them to drop in your lap. But I took

safety for granted, even in this age. I thought love was

enough."

Ann placed her palm flat against

the window. "My mother thinks the world is about to end."

"No more pain or misery." Dr.

Qaddoumi sounded almost wistful.

"That would be a good thing."

* * *

*

The hospital lost power just

before dinner. Ann and Lindsay were watching one of Mallory

Caine's movies when the screen dimmed and faded. The standby

generators didn't kick in and several alarms went off down the

hall.

"That's not good, is it?"

Lindsay asked, her voice slurred. "What if all the power's

gone?"

"Equipment breaks down

sometimes," Ann said, just as the TV brightened. "See? All

better."

A robot cart brought dinner, but

Lindsay swallowed only a few teaspoons of ice cream before

shaking her head.

"Please eat some more," Ann

said. "You'll feel better."

Lindsay turned her head. "No I

won't. Everyone says that, but it's not true."

"Then how about some of this

juice?"

But Lindsay refused that too,

and the soup, and everything else Ann offered her, all in a tone

that was petulant and whiney. Ann wanted to shake and scold

her, but what right did she have to be angry at her daughter?

She didn't have the strength to be angry anymore. Not at

Ersson, not at Daniel, not even at the cancer cells themselves.

Anger required energy, and it was all Ann could do to keep from laying her

head on Lindsay's leg.

"It's all right, honey." Just to

keep her hands busy, Ann began tidying up the bedside table.

She tucked some get-well cards into the drawer, then frowned.

"Where are your cat statues?"

"They ran away," Lindsay said.

"Last night. I heard them meowing, and then they jumped to the

floor and hopped out the window."

She'd probably had a fever

dream. Or maybe the figurines had gotten caught up in the

laundry when the nurses changed Lindsay's sheets, or some other

child had come in and stolen them. That last thought made Ann's

fists clench.

"Turn off the light, Mom. It's

too bright."

"Which light, sweetheart?" Ann

asked, but before she finished the sentence Lindsay was bucking

in the bed, her eyes rolled up and limbs flailing. Ann screamed

for help but the seizure was over almost as soon as it had

begun, and when the nurses arrived Lindsay was unconscious.

"Help her," Ann said, one hand

pressed over her heart. "Please help her."

Dr. Anderson came within the

hour. "We're not giving up," he said, but the look in his eyes

was bleak. Ann sat by the bed, flooded by grief and fear. She

clutched Lindsay's brooch and thought, save her, save her,

save her, but no god answered in the warm darkness.

The brooch tumbled from her numb fingers to the floor.

"Ann?" Daniel stood in the doorway, his face

haggard and pale.

"Are you real?" Ann whispered.

He squeezed her to his chest.

"It's all falling apart. Ersson's skylines. The security

satellites, telecommunications--I had to fight for the last seat

on a train out of Chicago, and a man was shot trying to squeeze

through the doors. God, they say that Washington's been--"

"Don't tell me." Ann soaked in

his scent and the strength of his arms. As much as she wanted

to stay furious at him, it was too much of a relief that he'd

finally come. "None of that is here and now."

He released her to stand over

Lindsay. The nurses had dressed her in her favorite nightgown

and a pink cap for her head. In the muted light they could see

a spiderweb of veins at Lindsay's temple, thin and fragile and

failing.

"Sweetpea," Daniel said, and

Lindsay's eyelids fluttered.

"I tried to pray," Ann murmured.

"I tried so hard."

Daniel tried again. "Sweetie,

wake up. Daddy's here."

But Lindsay did not wake. The clocks

ticked forward, the ward hushed but for occasional cries and padded

footsteps. At one point Ann saw fires burning a few blocks from the

hospital and heard the distant wail of sirens, but by dawn the flames were

gone and the smoke had dissipated. Behind her, Lindsay let out a long

breath and then went still.

"No," Ann said as monitors began

to blare and Daniel ran for help. "Lindsay, no!" she yelled, and

shook her roughly. Nurses poured into the room, their

conversation clipped and urgent, and pushed Ann aside. She

stood by the window and buried her head in Daniel's shoulder.

"She can't. Don't let her.

Daniel, don't let her--"

He pressed a kiss to her temple.

The room faced east across low buildings and

the flat prairie. For the first time in several months Ann felt a

warmth touch her face, and she lifted her eyes to see the sun peeking over

the horizon. The customary smog had cleared away, leaving the sky

clear and tinged with gold. The sight was so rare and unusual that she

stared until her eyes began to burn and water.

"Daniel, look," she said. As

she turned her foot brushed against the forgotten brooch on the

floor. Ann lifted it in her hand--how heavy it suddenly seemed,

and so very warm--and behind her, Lindsay coughed and cried out

as if she was a newborn all over again.

"Thank God," Daniel said.

"Too close," one of the nurses

said. "Call Dr. Anderson--"

The horizon exploded into

white-hot brilliance. For a split second Ann feared that

terrorists had somehow blown up the sun. The hospital began to

shake under a growing rumble of crumbing cement, twisting steel

and shattering glass. Just an earthquake, she

realized, not so bad, but then the building jerked and twisted like a rotten

tooth yanked out by an angry dentist, and this was something more

devastating than the shift of tectonic plates. Over the shriek of fire

alarms came the heartbreaking screams of children and adults.

"Mommy!"

Ann threw herself over Lindsay just as

another flash seared the sky. Split-seconds later the window shattered

and a concussive force rolled over them.

"Don't be scared!" Ann shouted,

though she herself was terrified. "It's okay--"

Another bomb fell, so close it might have

detonated in the parking lot. But that was ridiculous. A blast

so close would have vaporized them. More explosions rocked the earth

beneath them and sharp, burning shrapnel pelted down against Ann's skin.

In the dying hollows of her bones she could feel the concussion and doom of

a thousand A-bombs slamming into America, and in her ringing ears a thousand

thousand more shrieked across the sky toward the enemy.

She couldn't have said how long the

onslaught lasted, whether it took minutes or hours for the building to stop

swaying and for noise to fade from her bruised eardrums, but just as quiet

began to settle Lindsay murmured in awe against her chest.

"Wow," Lindsay said.

Half of the exterior wall was

gone, as was most of the ceiling. The nurses who had

resuscitated Lindsay were clustered in the far corner, weeping

and clinging tightly to one another. Somehow Daniel had managed

to entwine himself in their human knot. The pediatric ward

beyond the open door was thick with dust and rubble, and

survivors began to emerge in the aftermath. But it wasn't the

devastation that Lindsay was looking at. An ocean of warm

yellow light was washing down from the apex of the sky, so

bright and welcoming that an uncommon joy swept through Ann.

"It's Ra, Mom!" Lindsay wriggled

free. Her cheeks were plump and pink with unrestrained glee.

"He says he heard your prayers, and we should bring back his

hair!"

A great rustling sound filled the air.

A million fibers of hair--beautiful hair, in every color and texture

imaginable, stronger than steel--sprouted from under Lindsay's bed.

They wove themselves into a staircase that extended past the window and into

the blue sky all the way to the sun itself. Winged cats with

purple lilies in their mouths fluttered around the steps.

"Ann?" Daniel asked. Behind

him, children and their parents and the hospital staff began to

cluster in the doorway. "What the hell is going on?"

"I don't know." Ann's joy

faded. Surely she had gone insane. Or maybe she was regaining

sanity after a prolonged sojourn in a world full of sickness and

death, and self-destruction unprecedented. At the very top of

the stairs she could see her parents standing in the sun's

light. The dead children of Cloquet flanked them, flowers

in their hair.

"Mom, come on!" Lindsay tried to

dash up the stairs, but Ann caught her. "Dad, tell her!"

Daniel covered his mouth and

shook his head.

Dr. Qaddoumi wormed her way

through the crowd and gazed upward, perhaps seeing her dead son

and husband at the summit, or a promise of them in the Sun God's

embrace. Then she gazed back at her patients as if duty

compelled her to stay. Ann took a closer look, unwilling to

believe her own senses, but she couldn't discern a single scrape

or bruise on anyone. Jeannie Belson was clutched in her

mother's arms, her pudgy hands reaching for the sun. Tina

Willis and her surviving daughter, though covered with dust,

were grinning from ear to ear.

"Doctor?" Ann asked.

Dr. Qaddoumi's face was full of wonder. "I

think this is an invitation that can not be declined."

But such an invitation was not,

perhaps, a good thing. Ann turned to the ruins of Rochester.

An eerie silence blanketed the land. She imagined burned

corpses and charred skeletons stretching from one coast to the

other. Victims trapped in rubble, waiting for help that would

never come. Survivors stumbling about in a daze, slowly dying

of radiation sickness or starvation or exposure. Yet at the

same time a part of her knew that no hearts pulsed outside the

walls of this last refuge. She suspected no human hearts beat

within it, either. Mankind had started the grisly job of

annihilation, but the gods above had finished it.

"Mom, come on!" Lindsay

insisted.

Ann had put her faith in all the

expected places. Now she would put it elsewhere. She lifted

Lindsay into her arms, a feat she had not managed since her

daughter was much younger and smaller. She said, "Take my hand,

Daniel," and he did. With the brooch in her fist and her family

at her side she started stepping upward toward a beginning, or

an end, or someplace in between, some place in the sun.

About the Author:

Sandra McDonald is a former Navy

lieutenant and Hollywood wannabe. She has traipsed through the jungles of Guam,

braved the wilds of Newfoundland and conquered the Los Angeles freeways at rush

hour. Her work has appeared in Realms of Fantasy, Strange Horizons,

Chiaroscuro, Rosebud, Lone Star Stories, Andromeda

Spaceways Inflight Magazine and more. Visit her at her

website.

Story © 2005 Sandra McDonald.

|