The Hero and the Princess

by Sherwood Smith

Tam stomped the mud off

his boots and shouldered the inn's door open. Cold, rainy air swirled in

around him, causing the occupants of the common room to turn his way.

He paused on the

threshold to scan the room, one hand near the sword at his hip, the other

hand gripping the pack on his back that contained his travel gear, bow, and

arrows.

He saw three men

scowling at him, a couple of others busy with a game of skill, a woman and

children in one corner, and at the other tables a scattering of old folks

and young, but no threats, except maybe the three at the best table

alongside the fireplace, still glowering his way.

He slammed the door

shut. His heart thumped in his chest, but he kept his cold-numbed face

unrevealing as he watched the scowlers assess his size, his heavy

double-edged saber in its worn sheath, then turn back to their tankards,

none of them quite meeting his eyes.

The innkeeper bustled

up, wiping his hands. "Drink? Food?"

"And a room for the

night," Tam said, carefully hanging his water-warded cloak on a hook besides

the other patrons’ rain gear.

"I'll have to see your

coin," the innkeeper said, frowning at Tam's patched pack and worn leathers.

"I'll have ten gold

pieces by tomorrow eve," Tam said, keeping his voice firm. "This is the

village where the troll's been carrying off your livestock?"

Conversation in the room

stopped.

"That it is, that it is,

I'm sorry to say." The innkeeper scratched his chin through his beard, and

sighed. "Not just livestock. Two youngsters, both in the last week. Still,

you haven't earned that gold yet, and I need coin now."

Tam knew better than to

show any reaction. "The troll will be dead by tomorrow night," he said. "I

can pay you then."

One of the three bravos

at the fireside made a derisive noise.

"He can come join us,"

came a woman's voice.

The innkeeper did not

hide his relief. He nodded and disappeared in the direction of the kitchen.

Tam looked around, saw

the woman at the corner table gesturing to him. Feeling a little angry and a

little embarrassed at the reaction his announcement had caused--so different

from what he'd imagined during the long week's walk up the mountainside

through bands of stinging rain--he said nothing as he crossed the room.

The woman sat at a rough

peg table with a small girl and a half-grown boy, travel-worn tote bags

beside each. There was room on the high-backed bench beside the boy. Tam

adjusted his sword across his knees for fast access and sat down.

The boy's dark gaze took

in the sword, then he looked away, his indifference plain. Tam wondered if

the boy was a lackwit. When he'd been that age, just a glimpse of a fine

blade like that had made him mad with yearning.

"Nelath," the woman

said, smiling as she touched her bodice with a quick, graceful gesture.

"And you are--?"

"Tam," he said, hoping

that soon people would recognize him by reputation--and their voices would

repeat his name, maybe with a fine descriptor added. Tam the Brave. Tam

the Blade. Just like he'd listened to stories of great heroes all the years

he'd had to labor away at his father's carpentry shop, practicing his

swordwork during long evenings when everyone else was at leisure.

"Lornat and Elska,"

Nelath said, nodding first to the girl, then to the boy.

The children gave Tam a

polite nod, and went back to eating their food.

"May I ask where you're

from?" Nelath went on.

Tam knew it for a polite

question--the type to make conversation--but he'd decided that heroes didn't

come from dull villages like Bywater. You never heard commonplace details

about heroes in the stories. So he said, "I go anywhere there's trouble,

wrongs to be righted."

"A worthy goal," Nelath

said, cutting her meat before she took a bite. Tam, distracted by his

hunger, looked at her plate, and her hands. She had very dainty manners.

The innkeeper arrived

just then, and set a substantial meal before Tam, and a foaming tankard.

Nelath nodded her thanks to the innkeeper--again a gesture of trained grace.

Savory aromas rose; for

a time Tam had attention only for his food.

When his stomach let him

pause and look up again, the children had finished, and their plates were

neatly stacked. The boy Elska had taken from his tote-bag a length of

wood. Good balim, Tam noted, though of course he would never admit to

recognizing types of wood at a glance. Elska now took a carving knife out.

With slow, inexpert strokes he started carving chunks from his wood.

On the other side of the

table the girl pulled from her tote a battered lesson-book, and a slate and

chalk. She set them on the table and opened the book, all with an air of

long habit, as though she studied thus in mountainside inns every day. Tam

sipped at the good autumn brew, watching her follow with her finger the

handwritten words on the old book pages, then use her chalk to write them

out.

Nelath finished her meal

slowly, absently, pausing only when her daughter tipped the slate for her

mother to see. Nelath would either nod or shake her head; after each

response the child cleared the slate and worked again, either repeating a

phrase or going on to the next.

Both children looked

weary, Tam thought, as he sipped again from his tankard.

He looked up, met the

mother's gaze. She, too, looked weary. Both weary and tense. "Where you

from?" he asked.

Her smile was a mere

thinning of the lips, a quick glimpse of self-mockery. "We make our home

wherever we happen to find ourselves." So saying she laid her fork and

knife neatly across her plate, piled it atop her children's, and then pulled

from her own tote-bag some sewing.

The door opened then,

bringing a gust of chill air. Nelath and the two children all looked that

way, quick as startled birds. The newcomer, an old man, shuffled in and

addressed the innkeeper in a low voice.

Curious, Tam strained to

hear, but only a couple of words carried: "Horse," "foal."

Nelath dropped her gaze

to her sewing, and she started a hem with fast and neat stitches. She was

even faster than his own mother had been, Tam realized, her stitches

marvelously fine.

Her children, unbidden,

bent dark, curly heads back to their tasks.

"You're waiting for

someone," Tam said, putting together the clues at last.

He hadn't meant to speak

aloud, but Nelath only smiled a little, and nodded once. "My husband."

A sudden roar of

laughter from the three bravos caused another silence in the common room,

and quick, defensive glances from the other customers. The innkeeper

hovered in the door to the kitchen.

"More ale!" that was the

biggest one.

"Don't you think you've

had enough, Morvan?" the innkeeper asked in a coaxing tone, with a placating

smile.

"More! NOW! You fat old

potbellied rat, or I'll --"

"Right away, Morvan,"

the innkeeper said with fair bluster. "But you know your wife will be angry

come morning. Yours too, Perda, saying you’re a fine example for your

babes. And it's not just you who'll feel the edge of their tongues--"

A foul oath from Morvan

sent the innkeeper to the kitchen in silence.

Tam heard the three

cursing, but they seemed to have forgotten him. He sipped at his own ale,

and returned to his scrutiny of Nelath. There was something out of the

ordinary about her. She was plain to look at: wheat-colored hair with a few

gray strands bound up on her head; threadbare bodice, old gown beneath.

Somewhere between his age and his mother's. He sensed something amiss, but

he couldn't quite define it.

"You a seamstress by

trade?" he asked.

Nelath smiled again,

this time a real smile. "No. I haven't one calling, but I've learned a

little of several."

"What's this word,

Mama?" Lornat asked.

"Ves-ku-treh,”

Nelath sounded carefully, pointing to each letter in the battered book.

"One of the elementals. And those are--" she prompted.

Lornat sidled a glance

Tam’s way, lifted her chin, and stated with the conviction of one who knows

she’s right, "The elementals are the fundamentals of natural magic."

She looked maybe eight

or nine summers--if that. Her tone reminded Tam of himself when he was that

age. I know the eight death strokes, he'd announced to a passing

soldier once, and the man's laughter echoed harshly in his memory.

He said to Lornat in

what he hoped was an encouraging voice, "What are you studying?"

"I'm going to be a

healer-mage," the child said, her blue gaze earnest.

Tam whistled under his

breath. "That's a hard one. But you're not big enough to test for

apprenticeship yet, are you?"

"Three springs off,"

Lornat said. She wriggled on the rough bench, her whole body expressive of

her determination. "I will be ready when I face the Mistress of Mages."

Tam was aware of the boy

watching, though his slow strokes had scarcely paused. He was just getting

some height, tall and strongly made.

Tam said, "And you?"

"I'll try at the capital

end of summer," Elska said in a low voice. "I want to be a minstrel. You

have to make your own instrument and play it for the first test," he added,

pointing to the wood. "Here's to be my rebec."

Tam opened his mouth to

say that balim made a poor rebec. It was an easy wood to carve and its

grains were handsome to look at, but it had poor resonance. He shut his

lips. A hero wouldn't know anything about resonance, or balim, or rebecs,

or anything else so uninteresting.

Another roar from the

three drowned out any chance of further conversation. The screech of

wood--a chair being shoved back on the floor--followed by a tankard flying

across the room, snapped Tam's head round to the bravos' table.

The tankard hit an old

woman on the back of the head, knocking her forward across her soup bowl.

She cried out, soup splashing everywhere.

Tam felt battle lust

rush through him. Here at last was a cause! He stood, hand grasping his

swordhilt, but Nelath's thin, nail-bitten fingers reached across the table

to grip his wrist.

No.

She mouthed the word.

"Morvan!" the innkeeper

said, hustling out of the kitchen. "Blaek! Now you'll pay for--"

The drunken bravo stood

almost within sword's reach, waving his arms. "I won't pay for nothing, you

old sack o’ mulepoop--"

What happened next was

so quick that Tam hardly had time to react. He realized both of Nelath's

children had vanished. He looked around--and saw Nelath snap her fingers

lightly and point.

In the time it takes to

blink an eye Lornat darted out from under the table and crouched down.

Elska lunged up from next to his sister, pretended to trip, and knocked into

Morvan, who was just in the act of pulling a knife on the startled

innkeeper.

But Elska's elbow

blocked Morvan's knifehand in a neat disarm, and Morvan wavered,

off-balance, then fell over the crouched Lornat. He crashed to the floor.

His knife spun harmlessly under an adjacent table.

Lornat had rolled away

under another table, vanishing from sight.

The other two bravos

lunged to their feet, bawling drunken threats at the innkeeper.

The other young people

in the common room laughed at the sight of Morvan groaning on the floor, the

oldsters exclaimed questions no one listened to as they crowded around the

woman injured by the flying tankard. The angry innkeeper waved his hands,

trying to calm and placate.

The two bravos swung

around, glaring at those who’d laughed. One of them pulled a long hunting

knife and nodded at his friend. They took deliberate steps toward the

unarmed youths, who watched, silent now, and pale.

Tam's hand tightened on

his sword hilt--

Nelath rose to her feet;

Tam saw her left hand clenched.

There was a blur of

movement as Nelath and the bravos seemed to tangle up in arms and legs.

Tam, fascinated, kept his gaze only on her. Moving neatly and swiftly, she

elbowed one in the gut--robbing him of his breath--and kicked the side of

the other's knee, sending him windmilling for balance. She then opened her

left hand, releasing a puff of yellowish powder, and with her right made a

complicated swirling movement. The powder glowed briefly, all three bravos

snuffed it in--and fell atop Morvan who had just begun to climb to his

feet. All three began to snore.

"Here! Are you all

right, lady?" the innkeeper cried, springing forward.

"No harm done," Nelath

said, smoothing her skirt with a quick, elegant gesture--so quick, so

inadvertent it had to be habit, not intent. "I sent my children for more

thread just as these fellows rose--and I guess we got all tangled!"

She’s a noble,

Tam thought, realizing why Nelath's accent sounded so pleasing. She talked

like a high-born lady. Yet she and those children had just felled three

drunken, mad brawlers.

She gave a quick nod of

command. The children disappeared in the direction of the back door.

Nelath smiled at the

innkeeper. "Maybe you should just put these fellows in the barn and let

them sleep off their potations? I wager they'll waken with sorry heads come

morning."

"Aye," the innkeeper

said, looking down at them in puzzlement. “My ale has never done that

before. But we don’t know what they might have been drinking before they

came in.” He gave a shrug and added wryly, “One thing for certain, it’s with

crashing heads they’ll have to go off to labor come dawn.” He turned and

shouted toward the kitchen, "Ambie! Danac!"

Two long, stringy youths

emerged, both of them wearing aprons, and under the direction of the

innkeeper (who gripped Morvan's ankles) began to drag the fallen men out

into the rain.

Nelath reclaimed her

seat, and picked up her sewing as though nothing had happened.

The children were still

gone. Tam said, "That was a nice piece of work, but you didn't have to put

your children to it. I could have taken all three--drunk as they are." He

added the last in a low voice, feeling very sure now that bragging was not

going to impress her.

"I'm certain that you

could," she said. She looked up, her gray-blue eyes narrowed with

comprehension and humor. "But don't you think it's better for three young

men to wake up--perhaps sorrier and wiser, certainly with aching heads--and

go to earn their living, than for three families to be mourning?"

"Mourning," Tam

repeated.

"Did you not hear? Two

of those men have wives and small children. The other, I chanced to

overhear earlier, supports an ailing father."

Tam blinked, feeling as

if someone had tangled up his own feet, sending him off-balance. His inner

vision had been of swift sword-strokes, three mean drunks dead, and the

village celebrating his prowess before he even faced that troll up the

mountain.

He watched the last

man's head disappear through the back door as one of the innkeeper's boys

dragged him slowly out. Tam had seen only a roaring lout, someone ready for

a fight. He didn't think of such men having families--but they did. Every

man had a family, if only a mother.

He thought of his own

mother, weeping when he left. His father saying, Leave him be, Serah.

He has to be true to his own vision, we raised him to be true.

The children reappeared,

coming from the direction of the kitchen.

"I asked in the barn. No

one on the road," Elska murmured. He ducked under the table and slid into

his spot next to Tam. Then, in a lower voice, barely discernable over the

louder fuss on the other side of the room as the old woman protested that

she was all right, he said, "We've the liniments laid out, and salve, and

bandages."

Lornat too ducked under

the table and popped up into her place in the corner. She yawned fiercely,

and picked up her chalk again.

"Bandages? Did one of

you get hurt?" Tam asked, looking from one child to the other.

Lornat said softly,

"They're for Father. In case we need them."

"My husband is up the

trail," Nelath said.

Tam waited for further

explanation, but none came.

A sudden suspicion of

what the man might be doing caused him to say, "Who is your husband?"

"His name is Telnora,"

Nelath said.

Astonishment burned

through Tam. Telnora! Tel the Black Knight's Terror--Tel Kingslayer!

Could it be the same?

His inner vision was of a man just about his own age, but taller and

stronger, a vision that had been before Tam's eyes ever since he was old

enough to listen to stories. Telnora, who had appeared in the capital after

killing the evil Tower Mage's Black Knight; Telnora who fought the wicked

old King Alstrus in a duel, saving the kingdom from an invasion. He'd been

given the old king's daughter in marriage, and had gone on to great glory .

. . .

Tam had loved those

stories ever since he could pick up a sword.

And unlike Atticas the

Dragonslayer and Raniar Swordmaster, who had lived long ago, Telnora was

supposed to still be alive! Alive, and young and strong, because there

were new stories about him all the time--Tam had listened eagerly for each

bit of news of the hero all the years he grew up and practiced sword and bow

faithfully.

All the years . . .

He closed his eyes,

thinking back. It had been the summer he was seven when the old veteran of

King Alstrus’s border wars showed up in Bywater, looking for a quiet place

to settle, and Tam begged him for sword lessons. That was . . . twelve,

fifteen years ago?

He opened his eyes, and

looked again at Nelath. Here was a woman of maybe forty years, possibly

older. A woman who used the manners of a lady--

"Princess Nelatharian,"

he whispered.

Nelath put her finger to

her lips, and shook her head once. She was smiling, a smile more wistful

than merry.

Tam couldn't have spoken

if he'd wanted to. Was he really sitting across from a king's daughter?

How could she come to be stuck in a mountain village, dressed in worn

clothing?

He thought back, trying

to make sense of the stories that had come through Bywater. She'd been

married to Telnora, and, and, hadn't Telnora taken his place at the new

king's side? Yes, so the stories went. And the capital was quiet and

orderly, for Telnora reorganized the new king's guard, getting rid of the

corrupt guards of the old king. But just a couple of years ago when that

king died during a pirate attack on the royal fleet, and his young son took

the throne, stories about Telnora had changed. He was always vanquishing

this leader of thieves, or those marauders, or--three or four times--trolls,

which was why Tam had been so eager to get his own career begun with troll

vanquishing once he heard about the one up the trail from where he sat right

at that moment.

When he opened his eyes,

Lornat's head had fallen forward on her folded arms, and she breathed

deeply. Elska still worked at his wood, but his strokes were listless, and

he yawned frequently.

Nelath said, "Lornat

doesn't like the old stories. She likes happy endings."

"So you are the

Princess!" Tam whispered. He recalled her efficient moves in dropping the

three men. Her children, too. They'd been trained by an expert--so expert,

in fact, that the rest of the customers in the inn hadn't been aware of what

had really happened.

Why wasn't Elska being

trained as a hero?

"Yes," she murmured.

"Or, I was. When my brother ruled."

"But--I thought--" Tam

wasn't sure what he'd thought, except it had obviously been wrong.

"Tel knows nothing of

ruling, or of court politics," Nelath said, still with that slightly sad

smile. "My brother knew his value; my nephew, raised in the atmosphere of

court flattery, was afraid of him, and his new young queen professes to be

offended by Tel’s lack of ‘good blood.’ It was better to leave." She

glanced at her children. "And I found that I did not want my own young ones

growing up in the poisonous air of court."

Elska glanced up and

smiled briefly at his mother. Obviously none of this was new for him.

Tel swallowed. "So . .

. Telnora . . ." It was hard to say out loud the name of his revered hero.

"He's up the mountain fighting my troll--that is, the troll prowling there?"

Nelath nodded. "This is

why we wait."

And why the bandages,

and salve. But liniment?

Tam thought then of his

old vet trainer Helv, with one arm nearly useless, and his bowed back. The

villagers had made fun of him when he couldn't get off his bench without

groaning during the cold winters. Tam mentally counted up his years, and he

was startled to realize that his trainer and Telnora had to be the same

age. Old wounds, boy, old wounds, Helv used to say. They don't

ever heal, just harden.

"Fighting is all Telnora

knows," Nelath went on. "His father trained him from the time he could

walk; he had the very best swordmaster in the kingdom. When he was scarcely

ten, he could vault atop a horse's back and throw a javelin farther than

grown men. Accurate, too--but you were probably trained the same way,"

Nelath added.

Tam nodded, but he

secretly acknowledged he wasn't that good even now. Good enough to

defeat fools like those three snoring out in the barn, for he was young and

strong and fast, but his old vet had never claimed to be the best. I'm

alive, Helv had said, over and over. That's good enough.

"It's all he knows,"

Nelath repeated. "So this is how we earn our living, wandering across the

kingdom from trouble to trouble--for only kings can afford rich rewards.

Ten golds will just do to get us through the coming winter. In spring we’ll

be off again, looking for trouble. He'll do it until a younger, stronger,

and meaner trouble wins."

Tam looked at the little

family before him. The small girl asleep uncomfortably on the table, the

tired boy steadily working on his rebec. The woman who had once been a

princess, and now repaired castoff clothing, and waited.

Telnora had obviously

trained them all to defend themselves; Tam had no doubt that the princess,

old as she was, could have gutted the three fools herself. Maybe the

children could have as well, but instead she'd used disarming moves and a

bit of harmless magic that she must have learned during her days as a

princess.

And she and her children

sat, waiting either for the husband and father they obviously loved, or--he

remembered those anxious glances at the door--or for bad news. For the

encounter with something faster, stronger, meaner, than a hero.

Tam realized he was

still clenching his swordhilt. He freed his fingers, and turned to the boy.

"You should know," he

said, "before you go much farther, that balim is not a good wood for rebecs.

Fine enough for decorative frames or jewel boxes, but for a good resonance,

what you really need is a length of seasoned paak-wood. Now, let me show

you how to hold that knife for carving . . . ."

About the Author:

Sherwood Smith

began making books out of taped paper towels when she was

five years old, and at eight began writing stories about another world full of

magic and adventure--and hasn't stopped yet.

She studied

history and languages in college, lived in Europe one year, and has worked

in jobs ranging from tending bar--to put herself through grad school--in a

harbor tavern to various jobs in Hollywood. Married twenty years (two kids,

two dogs, and a house full of books) she is currently a part-time teacher as

well as a writer.

She has

twenty-five books out, ranging from space opera to children's fantasy, many

of which have appeared overseas in Russia, Israel, Denmark; also has

numerous short stories. "Augur's Teacher," from Tor, for adults and for

children, is the first 'officially' sanctioned sequel to L. Frank Baum's Oz

stories.

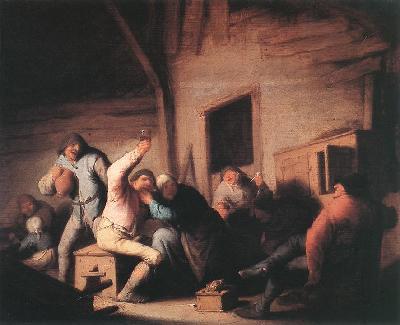

Story © 2005 Sherwood Smith. Print by A. J. van Ostadt, circa 1620.

|